A Conversation with Mathematical Consultant John D. Cook

Many articles, resources, and personal accounts address the transition from an applied mathematics career in academia to a position in business, industry, and/or government. These types of materials typically focus on traditional jobs within companies and organizations. However, mathematical consulting is a distinct career path with its own set of unique challenges and opportunities. John D. Cook—a consultant in applied mathematics, statistics, and technical computing—is a prime example of a success story within this niche field.

Cook began his career by earning his Ph.D. at the University of Texas, where he studied nonlinear partial differential equations. After completing a postdoctoral appointment at Vanderbilt University in the same topic, he left academia and worked as a software developer and project manager for several years. Cook joined the Department of Biostatistics at MD Anderson Cancer Center in 2000, where he first served as a software development manager and then as a research statistician. While at MD Anderson, his research centered on Bayesian statistics, clinical trials, and numerical algorithm development. In 2013, Cook left to start his own applied math consulting company.

Krešimir Josić of the University of Houston recently sat down with Cook to explore the nuances of founding and maintaining an independent mathematics consulting business. Here they share their conversation with SIAM News.

Krešimir Josić: You hold a Ph.D. in mathematics and have worked in both academia and industry for more than a decade. Why did you decide to become a consultant?

John Cook: For one thing, I love the variety that comes with consulting. I had worked for a software consultancy in the past, and there wasn’t much variety of work despite the variety of clients. Now I have a variety of clients and a variety of work.

I also wanted more agency over my income. There’s usually not much that salaried employees can do to change their income by more than a few percentage points per year, but business owners can decide how much money they want to make. Not entirely of course, but to a much greater extent than traditional employees.

Finally, I desired the security of multiple income sources. Salaried workers effectively have one client; if they lose that client, they lose 100 percent of their income all at once. As a consultant, I usually have several clients at a time.

KJ: How did you ensure that your business would succeed? Did you have any fallback plans in case it didn’t grow as fast as you anticipated?

JC: Looking for consulting work is not much different from looking for employment, and I figured that the effort I was expending to identify projects would also find job leads. Once I started consulting, several of my initial clients offered to hire me as an employee; my backup plan was to pursue one of those offers.

KJ: How do you determine which projects to accept?

JC: I’d recommend taking almost any project that pays when you first start, then gradually becoming more selective. I’d also recommend increasing your minimum project size over time. All projects take up some amount of transaction cost and mental overhead, regardless of their size; as a result, smaller projects are less profitable.

By initially casting a wide net, consultants can explore the types of available work. After a while, they may start to receive referrals in a certain area and begin to concentrate more in that particular subject. It pays to not be too set on one kind of work until you learn about existing demands in the field.

Risk analyst Nassim Taleb advocates for a barbell portfolio investment strategy. One end of the barbell consists of reliable income without much downside potential, which probably also means not much upside potential. The other end can be speculative or stimulating. I try to follow this strategy by maintaining a mix of reliable projects and more interesting projects. “Interesting” often means “unpredictable,” and consultants risk overloading themselves if they take on too many interesting projects at once.

KJ: I imagine that managing a team of consultants is quite different than managing a team in academia or most other professions. What unique challenges do you face in your position?

JC: I work with a loose network of consultants and collaborate with different people as needed, which is less effort than managing a standing team. Also, the work is very results-oriented. There are no office politics or other distractions that consume energy in large organizations.

I remember having a phone call one time with someone to whom I was subcontracting work and thinking afterwards, “I suppose that was project management.” It was so easy that I hadn’t thought about it in those terms. We simply discussed what needed to get done.

It’s a lot of fun to work with people who have clearly differentiated skillsets, which is the opposite of group projects in academia. The division of labor is obvious, and people don’t step on each other’s toes.

KJ: Tell us about some of your most interesting projects. Are there any that seemed routine and easy at the outset but actually turned out to be challenging? Or vice versa?

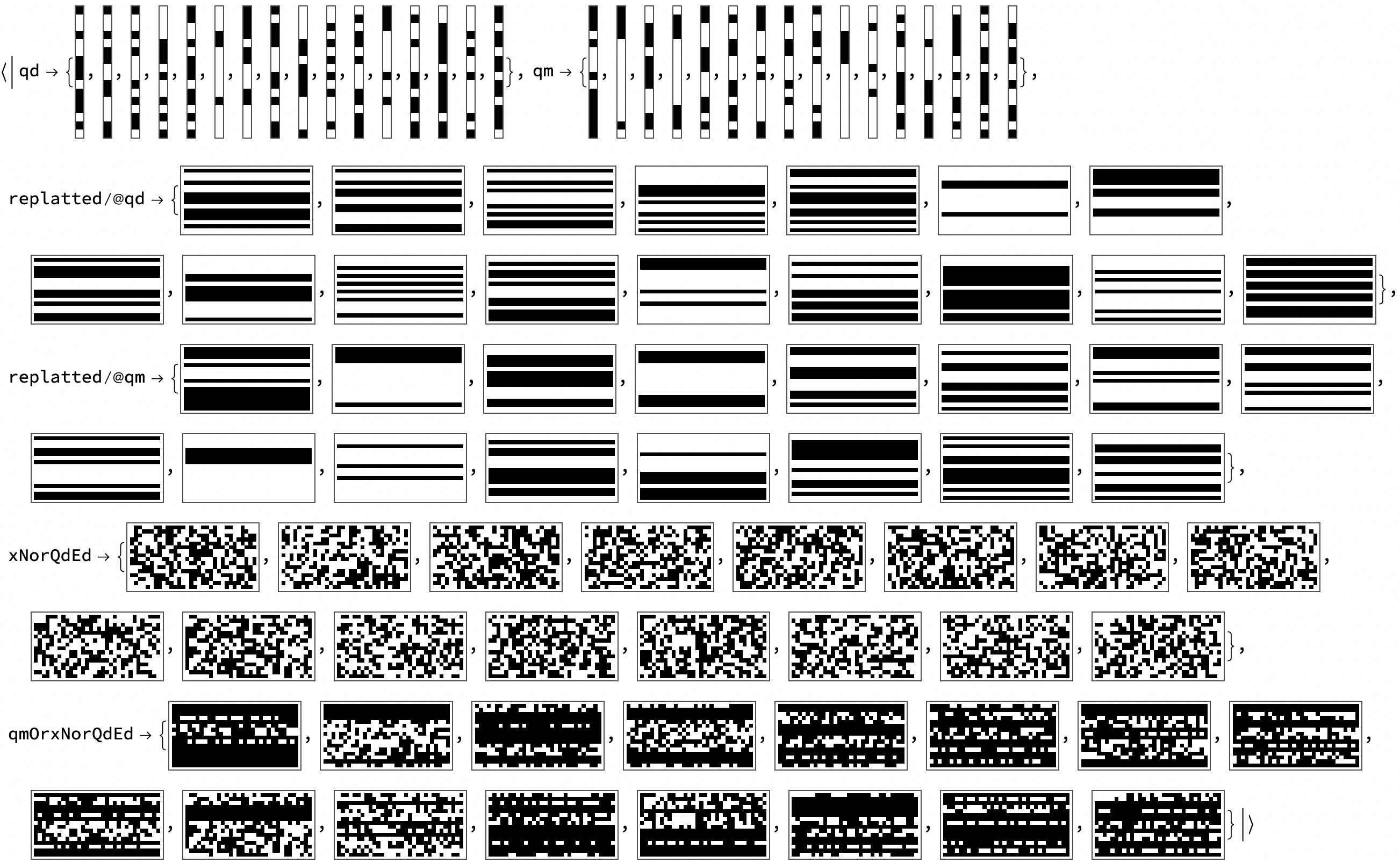

JC: Working with GSI Technology and their associative processing unit (APU) has been fun. The APU is a device that computes directly in memory rather than moving data back and forth between memory and central processing units. It’s like a large, three-dimensional array of bits. You can carry out thousands of computations in parallel by conducting bit-wise operations between slices of this array (see Figure 1). For the right problems, the APU can be much more efficient than conventional hardware in terms of both time and energy. The programming model is unique, meaning that familiar operations require new approaches.

One project that turned out to be much more challenging than expected was related to psychoacoustics; the client wanted to make machine noises less annoying. Doing so meant reducing the subjective perception of noise intensity, not simply reducing the noise as objectively measured in decibels. The relationship between sound pressure levels and perceived loudness is very nonlinear, and perceived loudness is not the only factor that contributes to people’s irritation towards a sound. Even though psychoacoustics is obviously subjective, general consistency exists in individuals’ perception of sounds.

Some projects turn out to be simpler than I anticipate. Academics are often disappointed if a solution is too simple because that means it might not be publishable, but private sector clients are delighted with simple solutions.

KJ: Which skills from your mathematical training and subsequent time in academia do you find most useful in your current work?

JC: Clients often need to have a conversation with someone who thinks like a mathematician. This means carefully defining terms and focusing on the largest ones, making implicit assumptions explicit, knowing when an approximation is or is not good enough, and so forth. But consultants can’t do these things until they speak their clients’ language. They must be able to comprehend their clients’ needs and use metaphors that they will understand.

John Tukey said that the best part of being a statistician is that you get to play in everybody else’s backyard. This sentiment is also true of applied mathematics in general. As a consultant, I’ve had the opportunity to learn a little bit about a lot of different areas.

KJ: Do you perceive a divide between mathematics and statistics in consulting? How much of your work deals with mathematical questions and how much involves statistics?

JC: Applied statistics may be closer to epistemology than mathematics. You have to question what you know, why you think you know it, and how confident you are (or should be) in that knowledge. You must make simplifying assumptions and determine whether they are justified. Statistical modeling is hard to do well. It’s easy to write down a model if you’re not overly concerned with the accuracy of your results. As the old saying goes, fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

Sometimes I get to work on statistical problems with crisp mathematical statements, such as finding an efficient way to compute something. These projects are fun because the epistemological concerns are someone else’s responsibility.

My work in applied mathematics has been more objective than my work in statistics. When you’re dealing with voltages or velocities, what you’re measuring (and what it means) is pretty clear. There’s much less anxiety around modeling, and your level of success at the end is usually obvious. I prefer mathematical work, but there are more statistical opportunities in consulting. These days I often hand over statistical projects to someone else; I work on statistical problems about data privacy but am moving away from medical statistics.

KJ: What advice do you have for those who are considering careers in consulting?

JC: When people ask me for advice regarding consulting, I tell them several things. One is that finding the work is harder than doing the work, assuming that the person in question possesses the technical skills for consulting. Another is that consulting can require more savings than you think, as consultants may face dry spells between projects. Also, clients—particularly large clients—can be slow to pay their invoices.

Many people think that they’ll start consulting on the side and leave their day jobs once the side business brings in enough income. That didn’t work for me, and I doubt that it works for many individuals. It’s hard to find the time or credibility to do much consulting while simultaneously holding down another job. At some point, you have to take the leap.

John is active on social media, with 18 technical Twitter accounts and a blog that has more than 3,000 articles.

About the Author

Krešimir Josić

Professor, University of Houston

Krešimir Josić is a John and Rebecca Moores Professor of Mathematics, Biology, and Biochemistry at the University of Houston.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.