A Novel View of an 18th-century Celestial Atlas

Phenomena: Doppelmayr’s Celestial Atlas. By Giles Sparrow. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, November 2022. 256 pages, $65.00.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the art of mapmaking and the science of astronomy advanced by leaps and bounds. During this period, art and science came together in celestial atlases: collections of maps and diagrams that depicted the universe as it was understood at the time. Giles Sparrow presents a masterpiece of this form—the 1742 Atlas Coelestis by Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr (1677-1750)—in his new book, Phenomena: Doppelmayr’s Celestial Atlas. Sparrow’s extensive tome reproduces Doppelmayr’s Atlas; enhances it with a wealth of additional illustrations; and explains its science, significance, and preceding and subsequent history.

Doppelmayr lived in Nuremberg, Germany, and worked as a mathematics professor at the Aegidien Gymnasium. He pursued a variety of scientific interests by making maps and globes, studying astronomy, grinding lenses and building telescopes, and conducting experiments with electricity. Doppelmayr wrote a number of books on topics in mathematics and astronomy (including sundials and spherical trigonometry) and penned a collection of short biographies for the mathematicians and scientists of Nuremberg. Though he is not known for making any original discoveries, he was nevertheless well respected in the research community of his day.

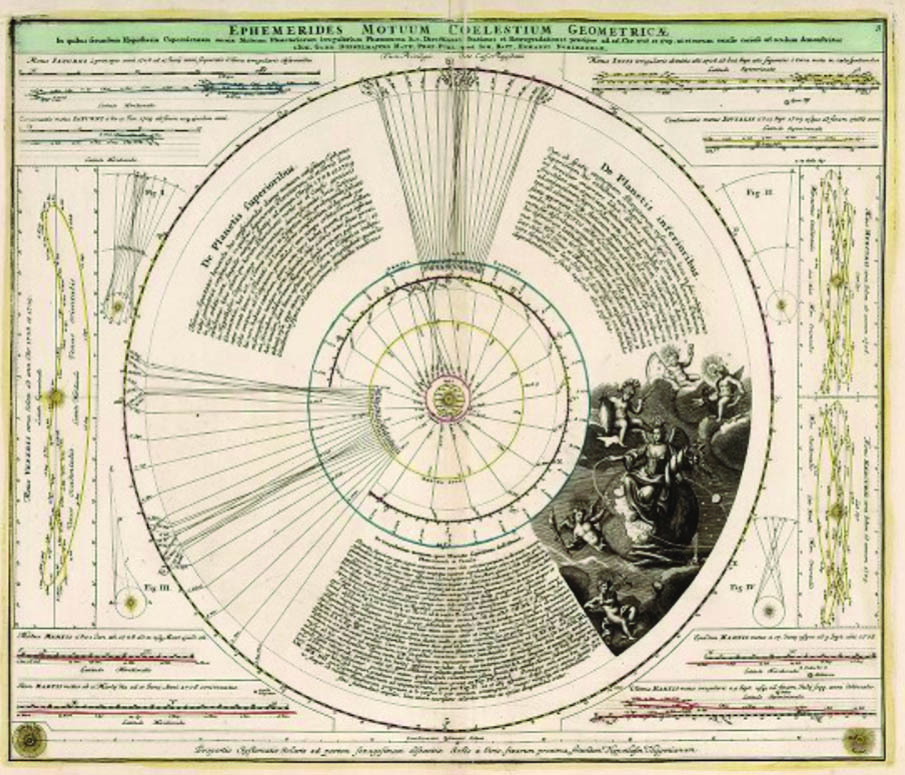

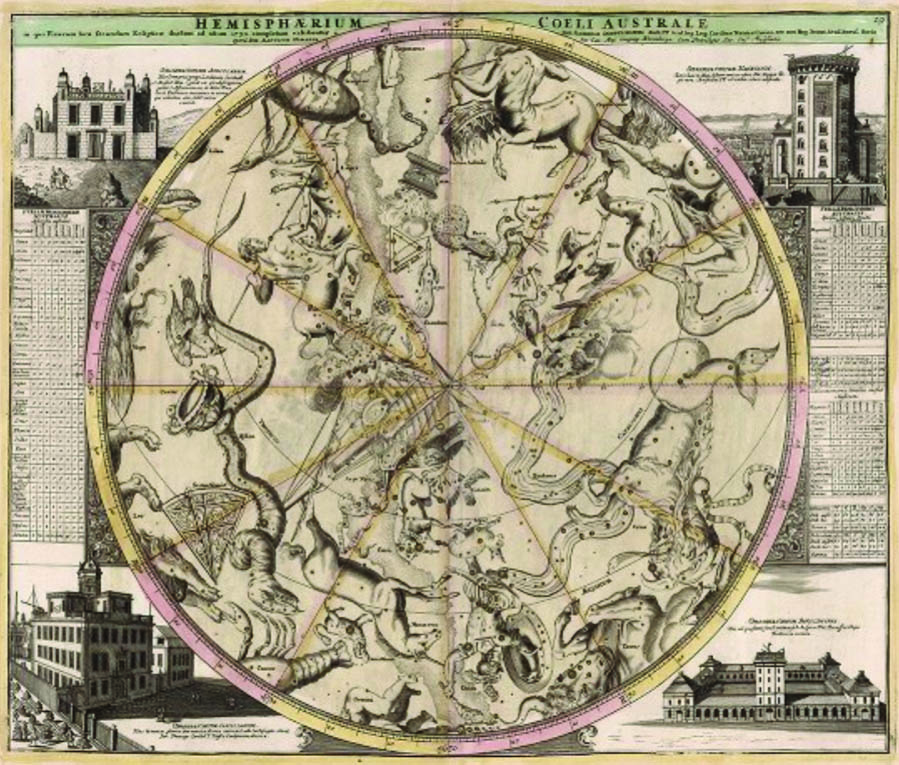

Doppelmayr’s original atlas consists of 30 large plates that use color in a moderate, unlavish way. Each plate contains one or two large maps in the center. Plate 1 provides an abstract presentation of Earth’s spherical geometry. Plates 2 through 10 describe the motion of the planets (see Figure 1) and offer a detailed presentation of Johannes Kepler’s heliocentric theory—in which the planets revolve around the Sun in elliptical paths—as well as Tycho Brahe’s geocentric theory, in which the Sun orbits the Earth and the planets revolve around the Sun. Plates 11 and 12 focus on the Moon, plate 13 explains eclipses, plate 14 describes Saturn’s rings and Jupiter and Saturn’s moons, and plate 15 serves as a map of the Earth that is divided into two hemispheres (each of which is presented as a circle). Plates 16 through 25 are star maps that portray the stars and constellations in a variety of projections; aesthetically, these are the richest plates (see Figure 2). Although the maps mostly lay out the same stars and constellations that were listed in Ptolemy’s Almagest and evident in many star maps over the intervening millennia, Doppelmayr does add some stars in the Southern Hemisphere that were not known to Ptolemy; his chart also includes six novas that were recorded over the preceding two centuries. Plates 26 through 28 address comets, and plates 29 and 30 depict the solar system from the perspective of the other planets in both Kepler’s and Brahe’s theories. Doppelmayr created the different plates at various points between 1707 and 1742.

Many types of additional materials encircle the large central images on the plates. All plates have hand-written explanations of the images in Latin, some of which are quite long. They also contain sizeable tables of data; for instance, the world map lists the latitudes and longitudes of roughly 100 European cities and 40 non-European cities, each of which is labeled with the name of the geographer who provided the information (Doppelmayr was generally very careful to appropriately credit his sources). The star maps include tables that enumerate the stars in every constellation, along with the stars’ celestial coordinates and a letter key that identifies them on the map. Meticulously drawn schematic diagrams illustrate various technical astronomical points. Doppelmayr crafted hand-drawn images of astronomical objects such as Montes Alpes (the lunar Alps), the rings of Saturn, and the Orion Nebula, many of which were copied from other astronomers (and again diligently credited). Two of the plates feature pictures of prominent observatories in their corners (see Figure 2), and several others incorporate illustrations of astronomical or scientific instruments—telescopes, sextants, pendulum clocks, and so forth—that are carried by putti.

Doppelmayr was clearly deeply interested in both the science and history of astronomy. He often utilizes multiple diagrams to explore alternative viewpoints; in addition to Kepler and Brahe’s theories of the solar system, other representations overview the theories of Ptolemy, Plutarch, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Porphyry, Johannes Cocceius, William Gilbert, and Sébastien Le Clerc. Doppelmayr frequently provides multiple comparative images of the same subject that are drawn by different astronomers at different times. For example, his Atlas includes four pictures of the markings of Venus, 11 of the markings of Mars, 10 of the markings of Jupiter, eight of the rings of Saturn, and two of the Orion Nebula. The frontispiece highlights Doppelmayr’s four astronomical heroes: Ptolemy, Nicolaus Copernicus, Brahe, and Kepler.

Sparrow’s Phenomena is both large (14 inches by 10.5 inches) and beautifully made. It reproduces each of Doppelmayr’s plates to fill a pair of facing pages. The subsequent pages also depict somewhat enlarged renderings of the plates’ individual, non-text components with brief explanations. Interested readers can view the plates of Doppelmayr’s Atlas online at the David Rumsey Map Collection, which allows users to enlarge details and better interpret Doppelmayr’s text (much of the text is in the horizontal center of the plate, which is difficult to read in Phenomena because it falls where the two facing pages curve in toward the binding). Sparrow offers an extended discussion of the astronomical and historical significance of each plate’s contents; these sections are clear, carefully researched, and very readable. Phenomena also contains many other illustrations from multiple contemporary and pre- and post-Doppelmayr sources. In addition, Sparrow supplies a short history of astronomy before and after Doppelmayr, a short biography of Doppelmayr himself, a timeline, a glossary, and an illustrated list of 18 major astronomers — from Aristotle to Edwin Hubble. Martin Rees, the U.K.’s Astronomer Royal, wrote the book’s forward.

Phenomena does not provide a translation, transcription, or detailed summary of Doppelmayr’s texts, and Sparrow’s general discussion does not clearly distinguish between information from Doppelmayr’s original Atlas and external matter. It would hence be quite laborious for readers like myself—who do not have a fluent knowledge of 18th-century astronomical Latin—to determine Doppelmayr’s exact thoughts on any topic; I have certainly not attempted it.

Three points about Doppelmayr’s book struck me as particularly remarkable. The first is the very fine detail and wealth of scientific issues that he engages, some of which I have already mentioned. Additionally, Doppelmayr included diagrams that show the effect of the Sun’s gravity on the Moon’s orbit, explain Ole Rømer’s 1676 measurement of the speed of light based on observations of Jupiter’s moons, explore various conjectures about the sizes of the planets and the Sun, describe the Moon’s libration, exhibit zodiacal light, and much more.

The second noteworthy point is Doppelmayr’s deep interest in Brahe’s alternative theory of the solar system; two full plates and multiple small diagrams illustrate various astronomical phenomena from Brahe’s theory. From a modern-day standpoint, this interest feels surprising in an atlas that was published nearly 200 years after Copernicus’ On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, 120 years after Kepler’s Epitome Astronomiae Copernicianae, 110 years after Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, and 55 years after Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Doppelmayr was committed to the heliocentric theory of Copernicus and Kepler, but he clearly considered Brahe’s theory to be an important alternative — at least at the beginning of his career.

Third, there appears to be an extraordinary omission; as far as I can tell, Doppelmayr never mentions Galileo in any form. While Galileo did not make any scientific contributions to the theory of planetary motion, his other contributions—including his world-famous, brilliantly written, heroic advocacy of heliocentric theory; pioneering use of the telescope in astronomy; and discovery of the moons of Jupiter, phases of Venus, craters of the Moon, and sunspots—unquestionably should have justified a large, prominent place in a book like this. Doppelmayr does not seem to have been biased against Italians; Giovanni Domenico Cassini, Francesco Bianchini, and others are featured prominently. The Catholic Church had completely dropped its opposition to Galileo by 1742—and Doppelmayr was likely a Protestant in any case—so that was not the issue. All I can suppose is that he had some personal animus against Galileo, who was indeed an extremely disputatious and unpleasant person and therefore easy to dislike. Nevertheless, it seems surprising for these traits to have been a consideration a century after Galileo’s death. Sparrow does not discuss this strange gap.

I must confess that I am a sucker for atlases, especially atlases with historical and scientific content. I spent many happy hours poring over Sparrow’s book and have enjoyed my time immensely. I learned a lot about the history of astronomy, and even a bit about its science as well. I am thus extremely grateful to Sparrow for putting this delightful book together.

Doppelmayr ends his Atlas with a haunting quotation from Seneca the Younger’s mystical scientific work, Investigations into Nature, and I will likewise do so:

Nature does not reveal all her secrets at once; her arcana are not shared with all indiscriminately, they are withdrawn and shut up within the inner shrine. For many ages to come, when our memory will have faded, are reserved those things for which those of our age will see one thing, and those who follow us, another. When, then, will these things be brought to our full knowledge? Great results proceed slowly, especially when labor ceases.

About the Author

Ernest Davis

Professor, New York University

Ernest Davis is a professor of computer science at New York University's Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.