Real-time Bayesian Inference With Full Physics Models: A Digital Twin for Tsunami Early Warning

Although rare, tsunamis can be extremely deadly and cause catastrophic socioeconomic losses that amount to hundreds of billions of dollars in damage. State-of-the-art tsunami early warning systems typically infer earthquake moment magnitude and hypocenter location, then use precomputed scenarios or simplified fault models to trigger tsunami forecasts within minutes. However, the seismic information on which these systems rely is based on simplified assumptions that often fail to capture the complexities of earthquake rupture dynamics [6], which can lead to delayed, missed, or false warnings.

To address some of the shortcomings of existing systems, we present a full-physics Bayesian inversion and prediction framework—a so-called digital twin [8]—that enables accurate, data-driven tsunami forecasting with dynamic adaptivity to complex source behavior. Our approach aims to improve warning capabilities by directly integrating real-time ocean bottom pressure data to constrain tsunami sources without relying on assumed fault geometry or magnitude. We utilize the acoustic-gravity wave equations—a partial differential equation (PDE) model that couples the propagation of ocean acoustic waves with surface gravity waves [7]—to model the tsunami dynamics of our digital twin. Based on this physics model, the inversion framework employs ocean bottom pressure data to statistically infer earthquake-induced spatiotemporal seafloor motion in real time. The solution of this Bayesian inverse problem is then used to simulate tsunami propagation toward coastlines and forecast wave heights at specified locations with quantified uncertainties.

![<strong>Figure 1.</strong> Topobathymetric map of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which runs from northern California to British Columbia. The shaded pink area illustrates the potentially “locked” portion of the megathrust interface, and the red line marks the trench where the subducting Explorer Plate, Juan de Fuca Plate, and Gorda Plate begin their descent beneath the North American Plate. Figure courtesy of [4].](/media/5lvhzmut/figure1.jpg)

This work falls into an important class of problems called inverse problems, which are fundamental to many fields of science and engineering. In a forward problem, the input parameters (e.g., initial or boundary conditions, coefficients, or source terms) are specified; the governing equations’ solution then yields the state variables that describe the system’s behavior. However, forward models typically contain uncertain parameters that are often infinite-dimensional fields that can vary in space (and possibly time). Inverse problems hence seek to infer uncertain parameter fields from measurements or observations of system states.

Infinite-dimensional inverse problems are usually ill posed, in that many parameter fields may be consistent with the observational data within the noise [2]. The Bayesian approach treats the uncertain parameter as a random field, and the inverse problem’s solution is the posterior probability distribution, which characterizes the probability that any parameter field is consistent with the data and prior knowledge. As such, the Bayesian framework is a very powerful technique for the characterization of uncertainty in the inverse problem’s solution.

But this power comes at a price: computing the full Bayesian solution is generally intractable for infinite-dimensional inverse problems that are governed by PDEs. For example, computing just the mean of the posterior formally necessitates numerical integration in the discretized parameter dimension; each evaluation of the integrand requires solution of the forward problem—which can take hours—and we need numerous forward solutions. The specific Bayesian inverse problem in question is the inference and prediction of tsunamis for early warning, which adds a real-time requirement to the aforementioned challenges. Our forecasting goal—to provide early warning in less than a minute—may seem futile, as state-of-the-art inversion methods would call for many years of supercomputing time to solve this problem. However, we achieve real-time performance through a combination of novel parallel inversion algorithms, advanced PDE discretization libraries, and the exploitation of leading-edge graphics processing unit (GPU) supercomputers.

Our digital twin framework [5] combines the following key ideas: (i) offline-online decomposition of the inverse solution that precomputes various mappings to enable the real-time application of the inverse operator and circumvent the need for PDE solutions during inversion; (ii) representation of the inverse operator in the data space instead of the high-dimensional parameter space; (iii) extension of this real-time inference methodology to the goal-oriented setting to predict quantities of interest (QoI) under uncertainty; (iv) exploitation of the shift invariance for the discretized differential operator to reduce the number of PDE solutions by several orders of magnitude; and (v) exploitation of this same property to perform efficient fast-Fourier-transform-based and multi-GPU-accelerated Hessian matrix-vector products (matvecs) [9].

The solution of inverse problems requires numerous Hessian matvecs, each of which comes at the cost of a pair of forward/adjoint PDE solutions. PDE solutions are computationally expensive for large-scale problems, which means that we cannot perform them in real time. One key innovation that enables real-time inference is the recognition and exploitation of the fact that the parameter-to-observable (p2o) map is governed by an autonomous dynamical system, which takes the seafloor velocity (parameter field) as input, solves the acoustic-gravity wave equations, and extracts the pressures (observables) at the sensor locations and observation times. Specifically, the acoustic-gravity model represents a linear, time-invariant dynamical system for which we can write the discrete p2o map as a block lower triangular Toeplitz matrix that corresponds to a time-shift invariance of its blocks. This invariance implies that (i) we can precompute the p2o map from only as many adjoint PDE solutions as the number of sensors; (ii) we can embed the block Toeplitz matrix within a block circulant matrix that is block-diagonalized by the discrete Fourier transform; and (iii) the p2o matvec becomes a block-diagonal matvec operation in Fourier space.

![<strong>Figure 2.</strong> Physics-based magnitude 8.7 dynamic rupture earthquake scenario for a margin-wide rupture in the Cascadia Subduction Zone. <strong>2a.</strong> True seafloor displacement field. <strong>2b.</strong> Snapshot of true seafloor acoustic pressure field with 600 hypothesized sensor locations. <strong>2c.</strong> Snapshot of true sea surface wave height. <strong>2d.</strong> Inferred mean of seafloor displacement. <strong>2e.</strong> Uncertainties that are plotted as pointwise standard deviations in meters of seafloor normal displacement. <strong>2f.</strong> Snapshot of reconstructed sea surface wave height with 21 locations for quantities of interest predictions. View animations of the <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=eQlHehX_u6k&feature=youtu.be" target="_blank">source</a> (seafloor vertical uplift and normal velocity), <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=-CPxuK6bebk&feature=youtu.be" target="_blank"> forward solution</a> (sea bottom pressure and surface wave height), and <a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=9OAPWumAd1g&feature=youtu.be" target="_blank">inverse solution</a> (true and inferred seafloor normal displacement). Figure courtesy of [4].](/media/dxlfzsu3/figure2.jpg)

Scalability is critical for the most expensive part of the offline computations: the adjoint PDE solutions. We discretized these adjoint wave propagation problems with the MFEM finite element library [1]. Next, we ran MFEM-based GPU simulations on large computer systems, including Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s El Capitan — the highest-ranked supercomputer on the Top500 list. Here, the MFEM solver demonstrated excellent scalability with up to 43,520 GPUs. The biggest problem involved more than 55.5 trillion degrees of freedom, which appears to be the largest reported unstructured mesh finite element computation.

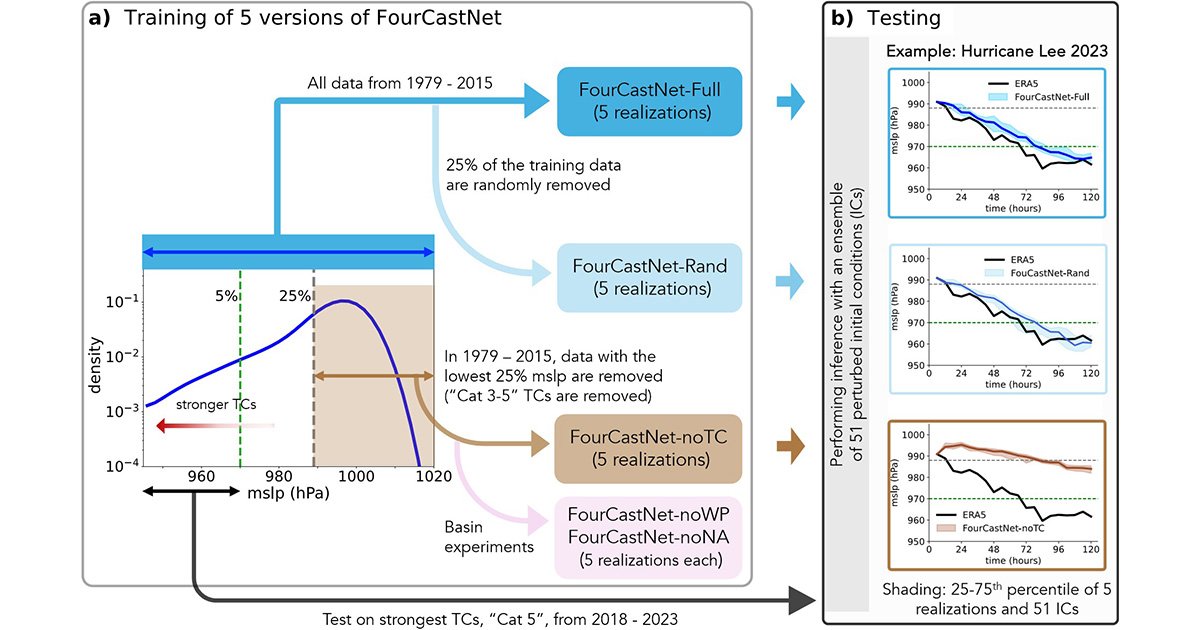

We applied our digital twin framework to the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ), which stretches 1,000 kilometers from northern California to British Columbia (see Figure 1). Because its last catastrophic seismic event was 300 years ago, seismologists consider the CSZ to be overdue for a magnitude 8.0-9.0 megathrust earthquake; paleoseismic and geodetic evidence indicates a recurrence interval of roughly 250 to 500 years. To assess our framework’s feasibility for near-field, real-time tsunami forecasting, we generated realistic seafloor displacements that capture the nonlinear interaction of seismic wave propagation and frictional rock failure during a magnitude 8.7 CSZ dynamic rupture scenario that we computed with the earthquake simulation code SeisSol [3]. We then used these “true” seafloor displacements as a source for our tsunami model to generate synthetic observational data with added noise at 600 different hypothesized seafloor pressure sensors. The sparse, noisy observations of acoustic pressure allowed us to solve the PDE-based inverse problem for the spatiotemporal parameter field with more than one billion parameters—which represent seafloor velocities during the earthquake—and make predictions of the QoI (sea surface wave height) at 21 forecast locations.

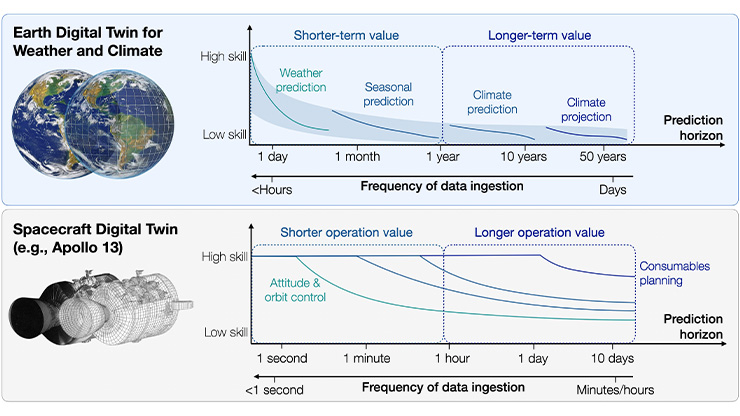

The offline phase, which we performed just once, required 621 adjoint wave propagations and took 538 hours on 512 GPUs. Given real-time data, the online phase requires just 0.2 seconds to exactly solve the billion-parameter inverse problem. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the results of the parameter inference and QoI prediction under uncertainty.

![<strong>Figure 3.</strong> Real-time quantities of interest (QoI) predictions with uncertainties, illustrated as 95 percent credible intervals (CIs) that were inferred from the noisy, synthetic data of 600 hypothesized seafloor acoustic pressure sensors for a margin-wide rupture in the Cascadia Subduction Zone. The QoI numbers in the upper right corner refer to a subset of the 21 QoI forecast locations in the inferred (reconstructed) sea surface wave height plot in Figure 2f. Figure courtesy of [4].](/media/1kknckye/figure3.jpg)

Given a sufficient number of ocean bottom sensors, this work ultimately enables real-time probabilistic tsunami forecasts for near-field events where conventional systems may fail due to delayed or inaccurate source characterization, such as a future magnitude 8.0–9.0 CSZ megathrust earthquake. Our digital twin framework accounts for complex rupture dynamics and tsunami wavefields in real time, under uncertainty, and without sacrificing the predictive power of the full three-dimensional wave propagation equations. This structure enables early predictions of inundation and evacuation zones within seconds, which is critical for life-saving responses where warning time is otherwise measured in minutes.

Autonomous dynamical systems arise in many different settings beyond geophysical inversion. Our Bayesian inversion-based digital twin framework is more broadly applicable to acoustic, electromagnetic, and elastic inverse scattering; source inversion for the transport of atmospheric or subsurface hazardous agents; satellite inference of emissions; and treaty verification, among other settings.

This article is based on Omar Ghattas’ Ivo & Renata Babuška Prize lecture at the 2025 SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, which took place last year in Fort Worth, Texas. The corresponding paper [4] was awarded the Association for Computing Machinery’s Gordon Bell Prize at the 2025 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage, and Analysis (SC25), which was held in St. Louis, Mo., last November.

Acknowledgments: This research was supported by U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Advanced Scientific Computing Research grant DE-SC0023171; U.S. Department of Defense Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives grants FA9550-21-1-0084 and FA9550-24-1-0327; U.S. National Science Foundation grants DGE-2137420, EAR-2225286, EAR-2121568, OAC-2139536, and RISE-2425922; and European Union 2020 Horizon grants 101093038, 101058518, and 101058129. Work was performed under the auspices of the DOE by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344 (LLNL-PROC-2004753). This research utilized resources from the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre, the Texas Advanced Computing Center, the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (ALCC-ERCAP0030671), and Livermore Computing.

References

[1] Anderson, R., Andrej, J., Barker, A., Bramwell, J., Camier, J.-S., Cerveny, J., ... Zampini, S. (2021). MFEM: A modular finite element methods library. Comput. Math. Appl., 81, 42-74.

[2] Ghattas, O., & Willcox, K. (2021). Learning physics-based models from data: Perspectives from inverse problems and model reduction. Acta Numer., 30, 445-554.

[3] Glehman, J., Gabriel, A., Ulrich, T., Ramos, M., Huang, Y., & Lindsey, E. (2025). Partial ruptures governed by the complex interplay between geodetic slip deficit, rigidity, and pore fluid pressure in 3D Cascadia dynamic rupture simulations. Seismica, 2(4).

[4] Henneking, S., Venkat, S., Dobrev, V., Camier, J., Kolev, T., Fernando, M., Gabriel, A.-A., & Ghattas, O. (2025). Real-time Bayesian inference at extreme scale: A digital twin for tsunami early warning applied to the Cascadia subduction zone. In SC ’25: Proceedings of the international conference for high performance computing, networking, storage and analysis (pp. 60-71). St. Louis, MO: Association for Computing Machinery.

[5] Henneking, S., Venkat, S., & Ghattas, O. (2025). Goal-oriented real-time Bayesian inference for linear autonomous dynamical systems with application to digital twins for tsunami early warning. Preprint, arXiv:2501.14911.

[6] LeVeque, R.J., Bodin, P., Cram, G., Crowell, B.W., González, F.I., Harrington, M., … Wilcock, W.S.D. (2018). Developing a warning system for inbound tsunamis from the Cascadia subduction zone. In OCEANS 2018 MTS/IEEE Charleston (pp. 935-944). Charleston, SC: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

[7] Lotto, G.C., & Dunham, E.M. (2015). High-order finite difference modeling of tsunami generation in a compressible ocean from offshore earthquakes. Comput. Geosci., 19(2), 327-340.

[8] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Foundational research gaps and future directions for digital twins. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26894/foundational-research-gaps-and-future-directions-for-digital-twins.

[9] Venkat, S., Fernando, M., Henneking, S., & Ghattas, O. (2025). Fast and scalable FFT-based GPU-accelerated algorithms for block-triangular Toeplitz matrices with application to linear inverse problems governed by autonomous dynamical systems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput., 47(5), B1201-B1226.

About the Authors

Stefan Henneking

Research associate, The University of Texas at Austin

Stefan Henneking is a research associate in the Center for Optimization, Inversion, Machine Learning, and Uncertainty for Complex Systems at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin.

Sreeram Venkat

Ph.D. candidate, The University of Texas at Austin

Sreeram Venkat is a Ph.D. candidate in the Center for Optimization, Inversion, Machine Learning, and Uncertainty for Complex Systems at The University of Texas at Austin’s Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences.

Veselin Dobrev

Computational mathematician, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Veselin Dobrev is a computational mathematician in the Center for Applied Scientific Computing at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. His research interests include numerical methods for partial differential equation discretization, finite element methods, arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian methods, preconditioning, adaptive meshing and remap, high-performance computing, and scientific visualization. He is a co-founder and developer of the MFEM library.

John Camier

Computational engineer and applied research scientist

John Camier is a high-performance computing computational engineer and applied research scientist. His work seeks to advance parallel computer architectures, optimize performance portability, and leverage high-order finite element methods for cutting-edge computational solutions.

Tzanio Kolev

Computational mathematician, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Tzanio Kolev is a computational mathematician in the Center for Applied Scientific Computing at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He is project leader of the MFEM library and served as director of the Center for Efficient Exascale Discretizations within the U.S. Department of Energy’s Exascale Computing Project.

Milinda Fernando

Research associate, The University of Texas at Austin

Milinda Fernando is a research associate in the Parallel Algorithms for Data Analysis and Simulation Group at The University of Texas at Austin’s Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences.

Alice-Agnes Gabriel

Associate professor, University of California, San Diego

Alice-Agnes Gabriel is an associate professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego. She is a geophysicist who combines simulations with data-driven techniques and theoretical analysis to increase safety during and after natural disasters.

Omar Ghattas

Professor, University of Texas at Austin

Omar Ghattas is a professor of mechanical engineering and the Ernest & Virginia Cockrell Chair in Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin), where he holds courtesy appointments in Earth and planetary sciences, computer science, and biomedical engineering. He is also principal faculty at UT Austin’s Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences and director of the Center for Optimization, Inversion, Machine Learning, and Uncertainty for Complex Systems.

Related Reading

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.