Can Artificial Intelligence Help Build Better, More Representative Teams?

All types of organizations—from research laboratories to technology companies—routinely assemble teams of individuals with complementary skills, experiences, and viewpoints. But while groups that mix different kinds of experience and perspectives can be more creative, they may also be harder to coordinate. So how can we form teams that balance variety and cohesion without leaving success to chance?

We utilize algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) to answer this question. Our work combines mathematical modeling, network science, and experimental social science to design and test computational systems that assemble teams with heterogeneous skill sets and balanced representation.

From Combinatorics to Collaboration

We choose to view the problem of team formation as a combinatorial optimization task. Given \(n\) individuals, how can we divide them into teams of size \(k\) that maximize several objectives, such as complementary expertise and existing social connections?

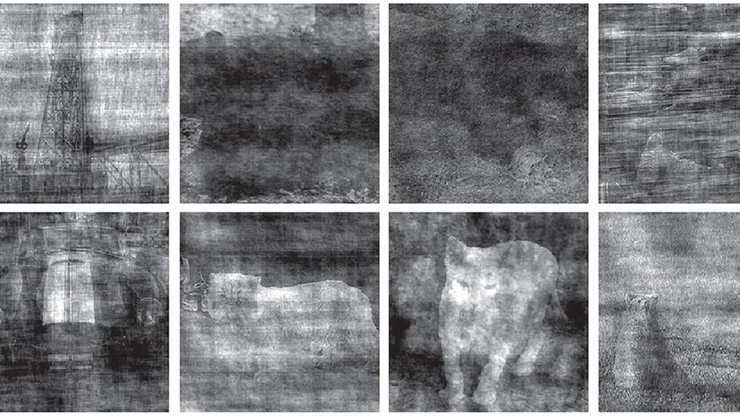

Because the number of possible combinations grows factorially with \(n,\) this task quickly becomes computationally intractable. Given this restriction, we implemented a genetic algorithm called the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) to efficiently search for team configurations that simultaneously optimize multiple objectives (see Figure 1). Each “generation” of the algorithm evaluates team combinations via the following two mathematical measures:

- Variety, which captures the level of distinction among team members across multiple attributes (e.g., skills, backgrounds, or demographic identifiers), as quantified via indices like the Blau index and coefficient of variation

- Familiarity, which reflects members’ preexisting connections in a social network.

NSGA-II evolves toward a Pareto front of optimal team configurations, where solutions that improve one property (say, familiarity) necessarily reduce another (e.g., variety). Rather than yielding a single “best” group, this method produces a range of well-balanced possibilities.

Testing Algorithms in the Real World

To move beyond simulation, we conducted a large-scale laboratory experiment with more than 380 participants who used MyDreamTeam—an AI-based online platform that assembles teams—for a creative problem-solving task. The platform served as a team recommender system, and we tested four versions of its algorithm that differed along two key dimensions:

- Agency: whether participants could choose their teammates or were automatically assigned to groups

- Representation criteria: whether the algorithm adjusted recommendations to promote balanced group composition.

This technique produced four experimental conditions:

- Random assignment: no agency and no representation criteria

- Algorithmic assignment: representation criteria but no agency

- Self-assembled teams: agency but no representation criteria

- Representation-bonus teams: both agency and representation criteria.

Participants then collaborated to design volunteer recruitment materials for a healthcare nonprofit organization, and independent judges rated the creativity of each team’s output.

When AI Nudges Collaboration

The results of our experiment revealed clear patterns. First, teams that had complete freedom tended to form homogeneous groups by selecting familiar, like-minded collaborators. In contrast, algorithms that incorporated representation criteria yielded more balanced team compositions. But perhaps most importantly, teams that combined agency with algorithmic guidance achieved the highest creativity scores.

These findings suggest that well-designed algorithms can nudge collaborations toward richer, more effective team structures without completely revoking control from the people who are involved. In other words, AI can augment human decision-making rather than replace it by connecting individuals with collaborators whom they might otherwise not consider.

Toward Human-AI Team Science

This type of research blends applied mathematics with human-AI collaboration. The mathematical foundations—namely optimization, network analysis, and algorithmic fairness—allow us to model and evaluate the complex process of team assembly.

As AI becomes increasingly embedded in professional and scientific collaboration, it is essential that we understand the potential influence of algorithmic designs on group formation. By combining computational precision with behavioral insight, we can develop systems that assemble teams for efficiency, representation, complementarity, and creativity.

Diego Gómez-Zará delivered a minisymposium presentation on this research at the 2025 SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, which took place in Fort Worth, Texas, last year.

About the Authors

Diego Gómez-Zará

Assistant professor, University of Notre Dame

Diego Gómez-Zará is an assistant professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Notre Dame, where he directs the Research in Networks and Groups Lab. His long-term goal is to design technologies that foster inclusive, effective, and innovative teamwork across science, education, and organizations. Gómez-Zará’s research—which bridges computational social science, human-computer interaction, and network science—focuses on how computational systems can help people collectively organize, collaborate, and innovate.

Noshir Contractor

Jane S. & William J. White Professor of Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University

Noshir Contractor is the Jane S. & William J. White Professor of Behavioral Sciences at Northwestern University whose research investigates the formation and performance of networks. He is a Distinguished Scholar of the National Communication Association; executive director of the Web Science Trust; and a fellow of the Academy of Management, International Communication Association, Network Science Society, American Association for the Advancement of Science, and Association for Computing Machinery. In 2022, Contractor received the Simmel Award from the International Network for Social Network Analysis.

Related Reading

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.