Maps of the Moon

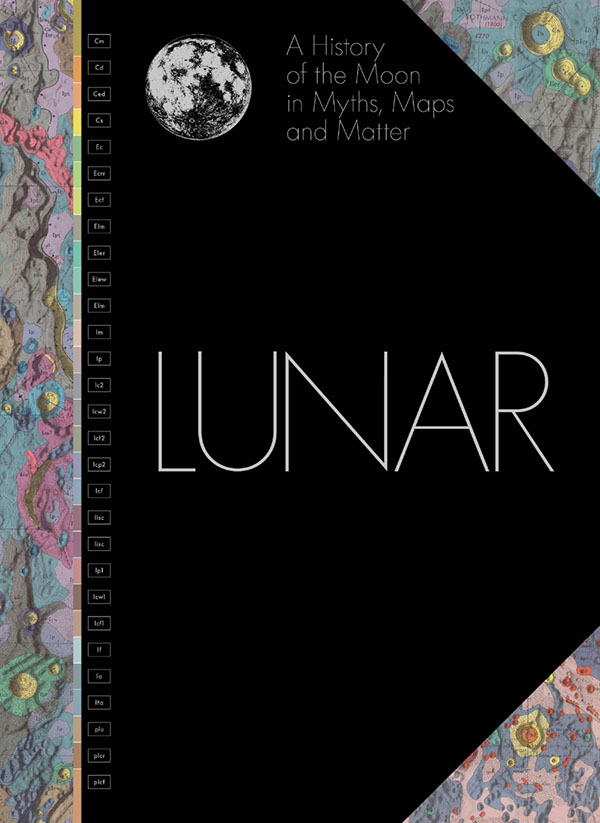

Lunar: A History of the Moon in Myths, Maps, and Matter. Edited by Matthew Shindell. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, November 2024. 256 pages, $65.00.

The topographical maps from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), an agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior, have been admired for decades by map enthusiasts and hikers alike. Printed on a scale of 1:24,000 (one inch to 2,000 feet), these beautiful maps are full of detail and marked with contour lines and physical benchmarks. They serve as delightful guides for an afternoon hike, fascinating subjects of study for a rainy day indoors, and suitable art pieces for framing and hanging on a wall.

However, the USGS maps are not limited to the U.S. or even planet Earth. Since 1961, USGS has also created maps of some of the solid heavenly bodies: planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Pluto; asteroids Ceres and Vesta; the four Galilean moons of Jupiter; four of Saturn’s large moons; Triton, the large moon of Neptune; and above all, our own Moon.

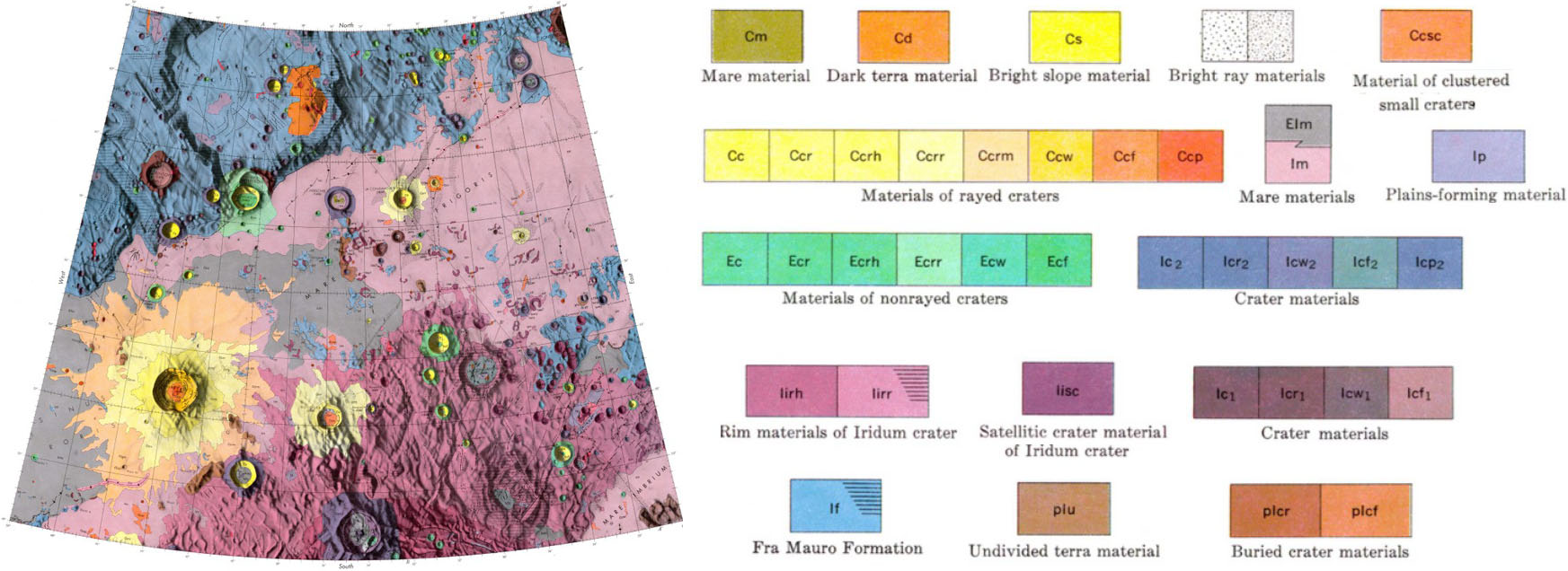

Between 1962 and 1974, the USGS Astrogeology Science Center produced a series of 44 maps that cover most of the surface of the near side of the Moon. The maps portray the region from 70° East to 70° West and 64° South to 64° North; the parts that are closest to the edge are omitted, presumably because scientists cannot observe them in sufficient detail from Earth. Each map is hand drawn on a 1:1,000,000 scale and in a head-on perspective (rather than from an Earth-based view). I would hence estimate that each map is about 25\(\times\)20 inches. Geological features are color coded, and every map is embedded in a larger, 35\(\times\)45-inch sheet with a great deal of text and graphical information: keys to the cartographic conventions, paragraphs of detailed geological information, and references to the literature.

These maps form the core of Lunar: A History of the Moon in Myths, Maps, and Matter, a new book that is produced by USGS and edited by Matthew Shindell. This large tome (14.5\(\times\)10.5 inches and 256 pages) is beautifully manufactured and lavishly illustrated. Each map is reproduced twice. First, the entire large map sheet is rendered as a half-page (9\(\times\)5 or 9\(\times\)6-inch) facsimile. At this scale, the map text is approximately a four-point font; squinting, straining, and holding the book close to my nose, my 68-year-old eyes can barely make it out. Second, each map is allotted its own two-page spread. The map itself is printed on the right page at about half of its original size (around 10.5\(\times\)9 inches), while the remainder of that page and the entire left page are filled with explanatory texts and relevant images: photographs from lunar orbiters, a list of notable manned and unmanned landings, and so on. Many further details are displayed separately in enlarged form. I will note that the colors in the printed book are less attractive than in the online version; for instance, the deep blue in the top left of Figure 1 is an unattractive muddy green in the physical copy.

In addition to the reproductions of the USGS lunar maps and discussions about their content and history, the book includes 31 two- to four-page essays on Moon-related topics that range from histories of science and the lunar landings to the Moon’s role in myth, religion, literature, and art. Each essay is lavishly illustrated; in all, the book must contain at least a thousand separate images, most of them remarkable and many of them beautiful. The authors of the vignettes are distinguished experts in their fields and comprise planetary scientists, historians, and popular science writers. These essays are interspersed with the maps and arranged in rough chronological order.

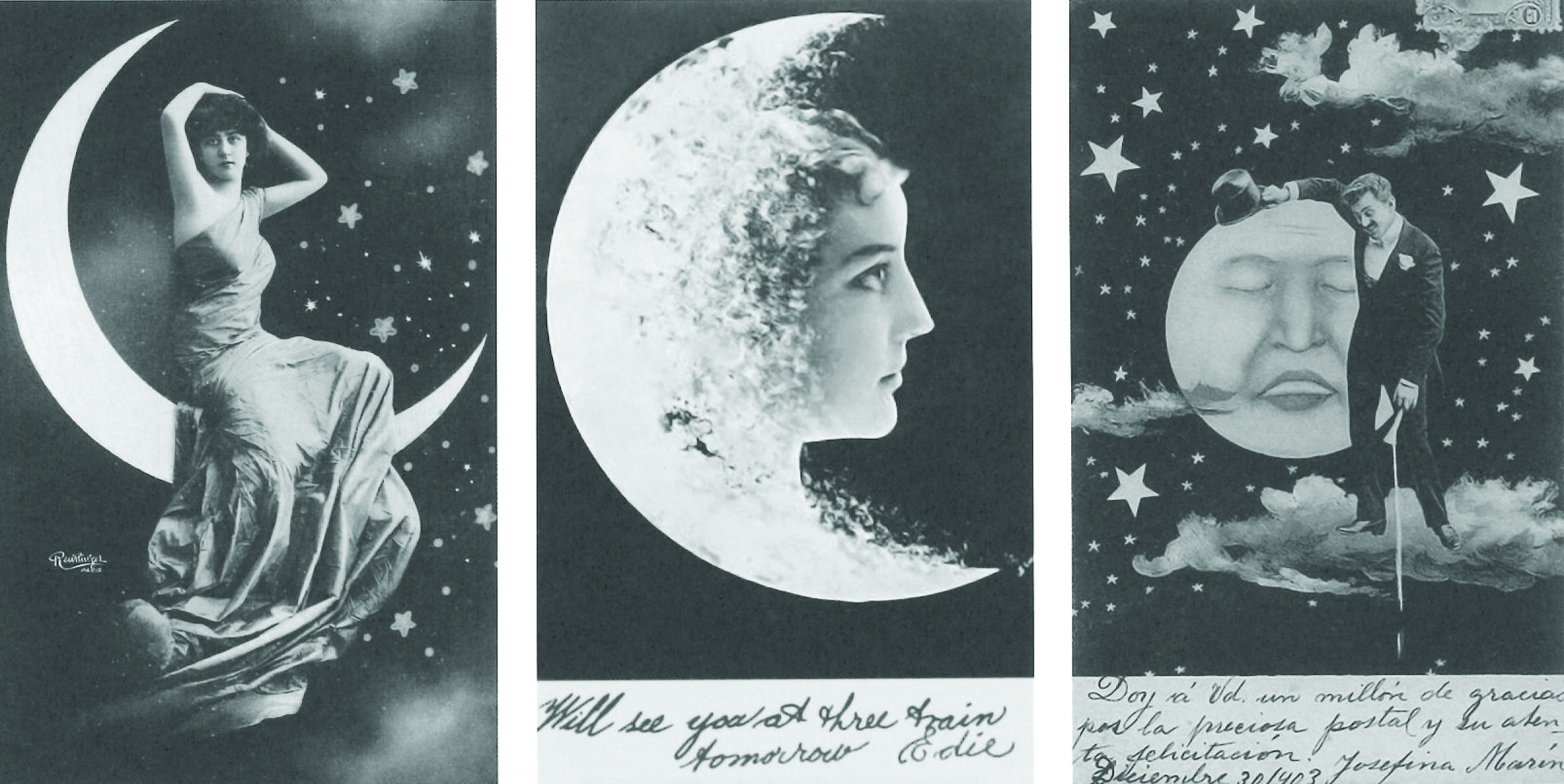

My favorite essay, at least in terms of the accompanying illustrations, is also the most frivolous. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries—once photography became popular and comparatively affordable—a fad emerged for visiting cards that featured a photograph of the card’s owner posed with a stylized crescent moon. The essay in question includes reproductions of 21 examples from an unidentified private collection (see Figure 2).

All in all, though, the exact point and intended audience of Lunar is unclear. A reader who wishes to learn about the Moon’s geology will find the account frustrating, as the book includes a lot of detail but does not provide a clear overall picture of what has been going on inside of the Moon for the last 4.6 billion years. A reader who hopes for an atlas would do better to consult the current USGS lunar maps—all of which are accessible online—or examine one of the several atlases of the Moon that are already available in print. The maps in this book are 50 to 60 years old and have been superseded in terms of both cartography and geology. Even a reader with a historical interest in these particular maps will generally have more success with the online versions. Many of the cartographical notations go unexplained in the main text and must be deciphered by working through the tiny facsimile on the reproduced map.

The far side of the Moon and the edges of the near side—that is, the parts of the surface that were not included in the original set of maps—get a particularly short shrift; Lunar only acknowledges them in one two-page essay with two small photographs and no maps of any kind. A book that seriously wanted to present lunar geography would hardly omit two thirds of the Moon’s surface in this way.

The illustrations that complement the non-map essays are marvelous, but the relatively brief texts often feel too short for the subjects that they attempt to cover. It is unsatisfying to read an article about scientific theories of the tides that jumps from Pierre-Simon Laplace to the present day with no mention of Lord Kelvin’s tide-predicting machine; or an article about the history of literary fantasies of life on the Moon with no reference to Cyrano de Bergerac’s 1657 The Other World: Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon; or an article about lunar astronomy with only a brief, dismissive comment on the lunar distance method of determining longitude—invented by Tobias Mayer and Nevil Maskelyne and refined by Nathaniel Bowditch—which was in practical use for close to a century.

My guess would be that the creators of Lunar started with a plan to publish the original maps as a celebration of the initial project, perhaps in honor of the 50th anniversary of its completion. Feasibly their second thought was that interest would be limited, so they decided to add the essays. The result is a volume that contains fascinating—albeit scattershot—content in the text and a treasure trove of Moon-related images, but not exactly a coherent book.

About the Author

Ernest Davis

Professor, New York University

Ernest Davis is a professor of computer science at New York University's Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences.

Related Reading

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.