Mathematics in Industry: What, When, and How?

Graduate students across the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) routinely face an important post-degree career decision: academia or industry? Unfortunately, companies rarely provide the title of “mathematician” in job postings, which can make it difficult for new Ph.D. candidates in applied mathematics to fully understand the day-to-day responsibilities of industry-based positions. But recent years have seen increased conversation and guidance about the importance of applied mathematics in business, industry, and government (BIG) settings. Furthermore, the boom of “big data” has created numerous quantitative science jobs in organizations that specialize in healthcare, medicine, government security, and defense research. Given the wide range of current opportunities, applied mathematics graduates must think about which career paths are best suited for them.

In 2018, SIAM published BIG Jobs Guide: Business, Industry, and Government Careers for Mathematical Scientists, Statisticians, and Operations Researchers to help students and early-career mathematicians understand the growing industry job market. Authors Rachel Levy, Richard Laugesen, and Fadil Santosa agree that the most common job titles for mathematicians include “data scientist,” “analyst,” and “software engineer,” though other “quantitative”-based titles are also abundant. It is thus wise for students to market themselves as more than simply mathematicians. “One misconception is that you can present yourself as a mathematician and people will automatically know what you bring to the table,” Levy said. “Job seekers should practice describing the types of problems that interest them and the ways in which they have tackled a problem with approaches that might be relevant to a prospective employer.” Another common misconception is that industry jobs lack intellectual challenge or are focused on simple “number crunching” tasks. Laugesen offered an alternative viewpoint. “The problems in industry and government tend to require a broad range of expertise,” he said. “The mathematical scientist must therefore interface with team members who possess quite different conceptual toolboxes.”

One of the starkest differences between academic and BIG settings is the quantity of open positions. While most major metropolitan areas—and many smaller regions as well—typically offer ample satisfying job prospects in industry, academia is less straightforward. Early-career academic professionals often must accept what is available, rather than target specific areas. Moreover, BIG jobs generally have clear-cut working hours, whereas the burden of teaching, advising students, submitting grant proposals, and conducting personal research can greatly exceed the 40-hour workweek in academia. However, academic jobs frequently provide more intellectual freedom for mathematicians to pursue their own research endeavors, while BIG positions are commonly created and funded to address specific problems.

Switching from Industry to Academia

Though the switch from industry to academia might be uncommon, it is certainly possible. Laura Ellwein Fix, an associate professor of mathematics at Virginia Commonwealth University, spent several years in industry before returning to school and pursuing her Ph.D. in applied mathematics. “My job as a quality engineer was not what I expected,” Ellwein Fix said. “I thought it would entail more long-term scientific problem solving, but I found that needs in manufacturing were primarily customer-driven firefighting.”

Based on both her prior interest in industry and Ph.D. research in mathematical biology, Ellwein Fix completed an internship at a large pharmaceutical company while doing graduate work. Although the experience was both engaging and enjoyable, she ultimately accepted a postdoctoral position in bioengineering at Marquette University before securing an academic appointment in mathematics. “The reward of deriving mathematical bases for scientific phenomena while being able to conduct outreach and teach young professionals solidified my desire for an academic position,” she said. Ellwein Fix appreciates the freedom to chase her own research goals. She also commented on the varying time flexibilities of industry versus academia. In her industry job, Ellwein Fix was given brief timelines to complete projects and allotted only a short period to brainstorm and problem solve. Her academic position, however, permits a semi-flexible schedule that allows her to spend the appropriate time addressing new ideas in mathematical physiology while still meeting reserach, teaching, and administrative deadlines and maintaining a healthy work-life balance. The switch from industry to academia was therefore beneficial for Ellwein Fix, as it provided insight into both job markets that helps her advise undergraduate and graduate students on their career goals.

Switching from Academia to Industry

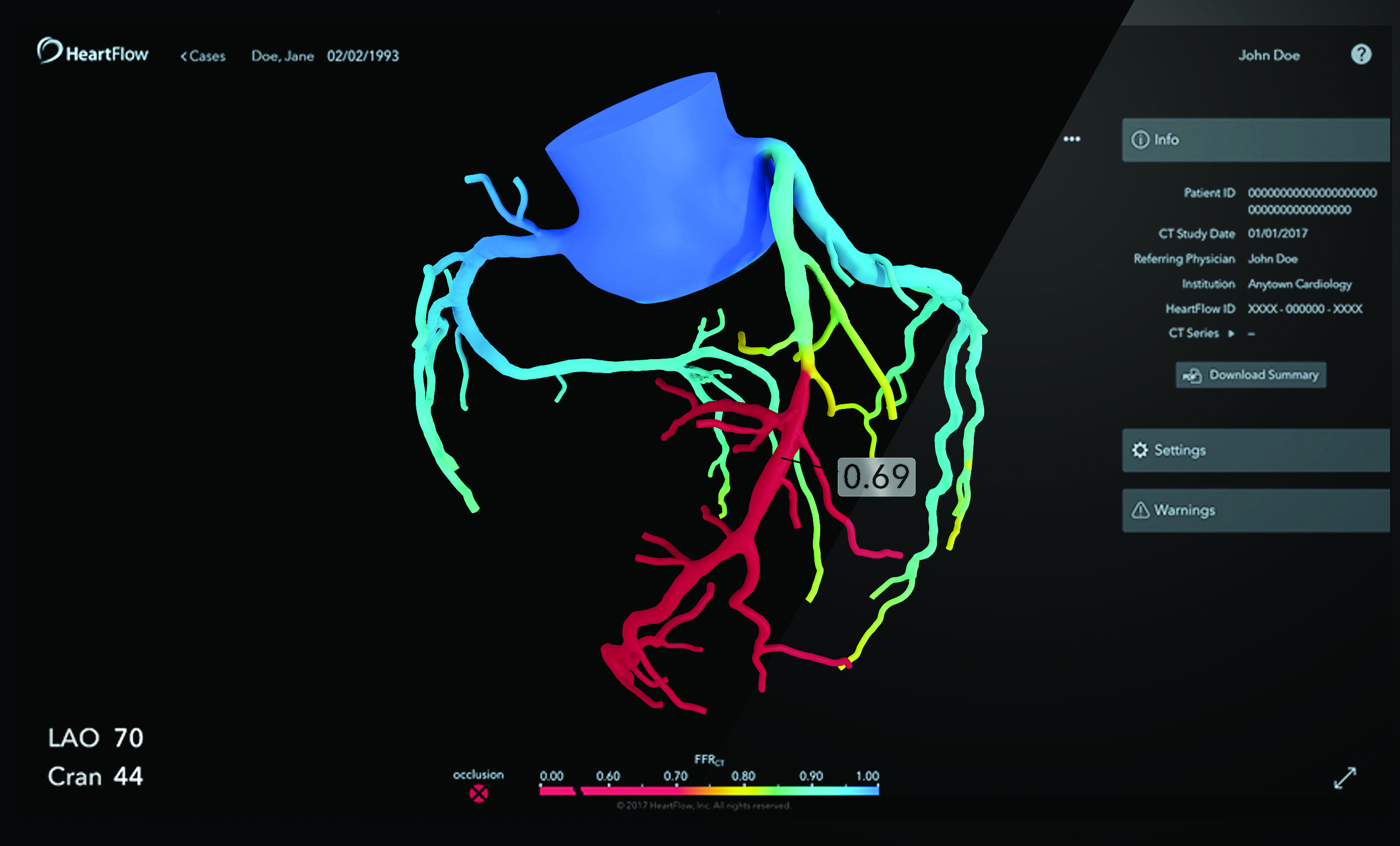

Conversely, switching from academia to BIG is more common. Charles Taylor left his position as an associate professor at Stanford University to cofound HeartFlow, a company at the intersection of computational modeling, artificial intelligence, and healthcare (see Figure 1). Taylor had previously worked in industry for several years after obtaining his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, before opting to pursue a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering at Stanford. His Ph.D. thesis focused on the integration of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) with medical imaging modalities to predict blood flow and pressure in patient-derived geometries. After becoming a professor at Stanford, Taylor saw a chance to bring his ideas to the public through the healthcare field. “I went into academia because there was an opportunity to work on a hard problem for a long time, which a lot of industries weren’t ready for yet,” Taylor said. “I decided to start HeartFlow because I was at a point where I could pursue the ideas from my Ph.D. on a larger scale.”

HeartFlow has since provided a new FDA-cleared tool for diagnosing and managing coronary artery disease, all driven by Taylor’s initial work in cardiovascular CFD and the growing field of machine learning (see Figure 2). “Use your thesis as a starting point for your career,” Taylor said. “Ask yourself three things: What do you love? What are you good at? And what does the world need? Know these three things and always be flexible; what you start doing after your degree will change over the years.”

Which Should I Choose?

The choice between a career in academia or BIG ultimately depends on individual preference, research area, and desired lifestyle. Given the complexity of the decision, SIAM has taken numerous steps to better educate undergraduate and graduate students on the nuances of BIG careers. For example, mathematical sciences students and faculty can utilize SIAM’s Visiting Lecturer Program, which provides the community with a roster of experienced mathematicians and computational scientists from both academia and BIG that are willing to speak to students about their experiences. The Tondeur Initiatives, funded by Philippe and Claire-Lise Tondeur in 2018, also provide a repository of programming that aligns with the BIG Math Network and pertains to BIG internships and career opportunities.

One obvious limitation of academia is the job market itself. “The number of tenure-track positions remains fairly flat, while the number of other types of positions is exploding,” Levy said. While this remark is true in typical years, the COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated the situation. In fact, a recent article in Science reports a 70 percent decrease in STEM tenure-track openings in the U.S. when compared to the previous year [1]. Taylor suggests that new applied math Ph.D.s consider possible academic employment in departments beyond mathematics. “Interdisciplinary scientists can be qualified for different department positions,” he said. For instance, experts in uncertainty quantification may find suitable placement in mechanical engineering departments, whereas those who excel at mathematical biology might be ideal candidates for biostatistics or developmental biology departments. The same logic applies to industry positions, where the role of “data scientist” takes many different forms depending on whether one is employed at a national laboratory or social media company.

Ellwein Fix encourages early-career mathematicians to use conferences—including virtual gatherings—as opportunities to learn more about academic versus BIG careers. “Don’t hesitate to contact the people you meet at conferences,” she said. “Senior researchers and professors expect emails from students who ask to meet during conferences, so be sure to reach out to those who are making an impact in your field of study.” Ellwein Fix still communicates with multiple BIG contacts that she encountered at prior conferences; they often inform her of new industry jobs for her own students. “Many of my career opportunities came from staying in touch with individuals I met during my Ph.D.,” she said. Some conferences also host career fairs—the 2021 SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering is one such example—which are great ways for students to learn about industry jobs at different companies. Representatives from these companies can also answer questions about work-life balance, job growth, and benefits.

Taylor likens the entry-level, assistant professor position in academia with having a startup company. “As an assistant professor, you have numerous new responsibilities to which you must adapt, all while trying to obtain your own funding,” he said. This is especially true at Research 1 institutions. Industry positions are a bit different. “You will likely have to stay in your own lane in an industry job at a big company,” Taylor continued. “It can be easy to get stuck in the same role, so it is important to have a job at a company where you know you can grow.” Because both academic and industrial or government jobs have their own pros and cons, new graduates should assess their individual goals inside and outside of their professions.

Many resources are available for current and recent graduate students who are deciding between careers in industry and academia. The BIG Jobs Guide and BIG Math Network provide information about opportunities outside of the realm of academia, in addition to resources about BIG careers. Additional information is accessible via SIAM’s Career Resources page.

References

[1] Langin, K. (2020, October 6). Amid pandemic, U.S. faculty job openings plummet. Science. Retrieved from https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2020/10/amid-pandemic-us-faculty-job-openings-plummet.

About the Author

Mitchel Colebank

Ph.D. Candidate, North Carolina State University

Mitchel Colebank is a Ph.D. candidate in the Biomathematics Graduate Program at North Carolina State University. Upon receiving his Ph.D. in the spring of 2021, he will begin a postdoctoral research position in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of California, Irvine.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.