Pulmonary Digital Twins for Mechanical Ventilation: Advancing Multiscale Models to Predict the Response of Failing Lungs

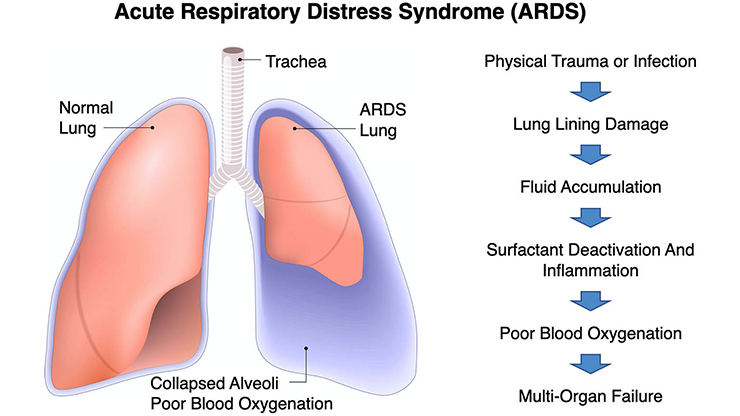

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, few people were familiar with mechanical ventilators. However, the global outbreak in 2020 brought unprecedented attention to the critical role of these machines in modern healthcare. The ventilator—formerly a specialized device primarily associated with intensive care units (ICUs)—rapidly became a symbol of life-saving intervention for patients with COVID-19; within a few months, the worldwide manufacture and delivery of ventilators surged to unprecedented levels. However, those with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) still faced a high probability of death even with mechanical ventilation, as evidenced by ventilator mortality rates of up to 90 percent during the pandemic [1].

Clinical outcomes in mechanical ventilation remain suboptimal, and recent research indicates that the general mortality rate of ARDS patients has not significantly decreased since the implementation of protective strategies from a 2000 ARDS Network study [5, 14]. While the underlying causes of this high mortality rate remain under debate, the ICU community agrees that the only way to improve clinical results is through personalized mechanical ventilation therapy. As such, computational modeling—and the development of digital twins in particular—can play a crucial role in delivering more effective treatment to patients who rely on ventilators.

Mathematical models of mechanically ventilated lungs have evolved significantly due to a steady increase in computational power and a deeper understanding of the biomechanical and biological processes that govern the respiratory system's response to mechanical ventilation. One of the simplest and most popular mathematical representations of the lung response is the single-compartment (SC) model. The SC model utilizes a systems approach that represents the airways and lungs with resistive and elastic elements in series [3]. The power of this model lies in its popularity among both respiratory physiologists and clinicians. Remarkably, parameters of the SC model—such as respiratory compliance and airway resistance—are displayed by modern mechanical ventilator monitors and commonly used in ICUs to inform clinical decisions during treatment.

But despite the advantage of researcher and practitioner familiarity with the SC model, it only represents the overall response of the respiratory system and cannot deliver regional insights into lungs that are spatially heterogeneous. Furthermore, we can only determine parameters in the model via an inverse problem that relies on data from the mechanical ventilator; thus, we cannot predict parameters before a patient is connected.

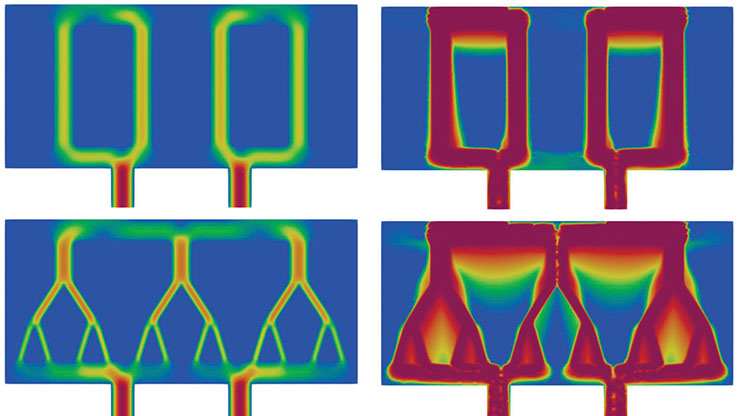

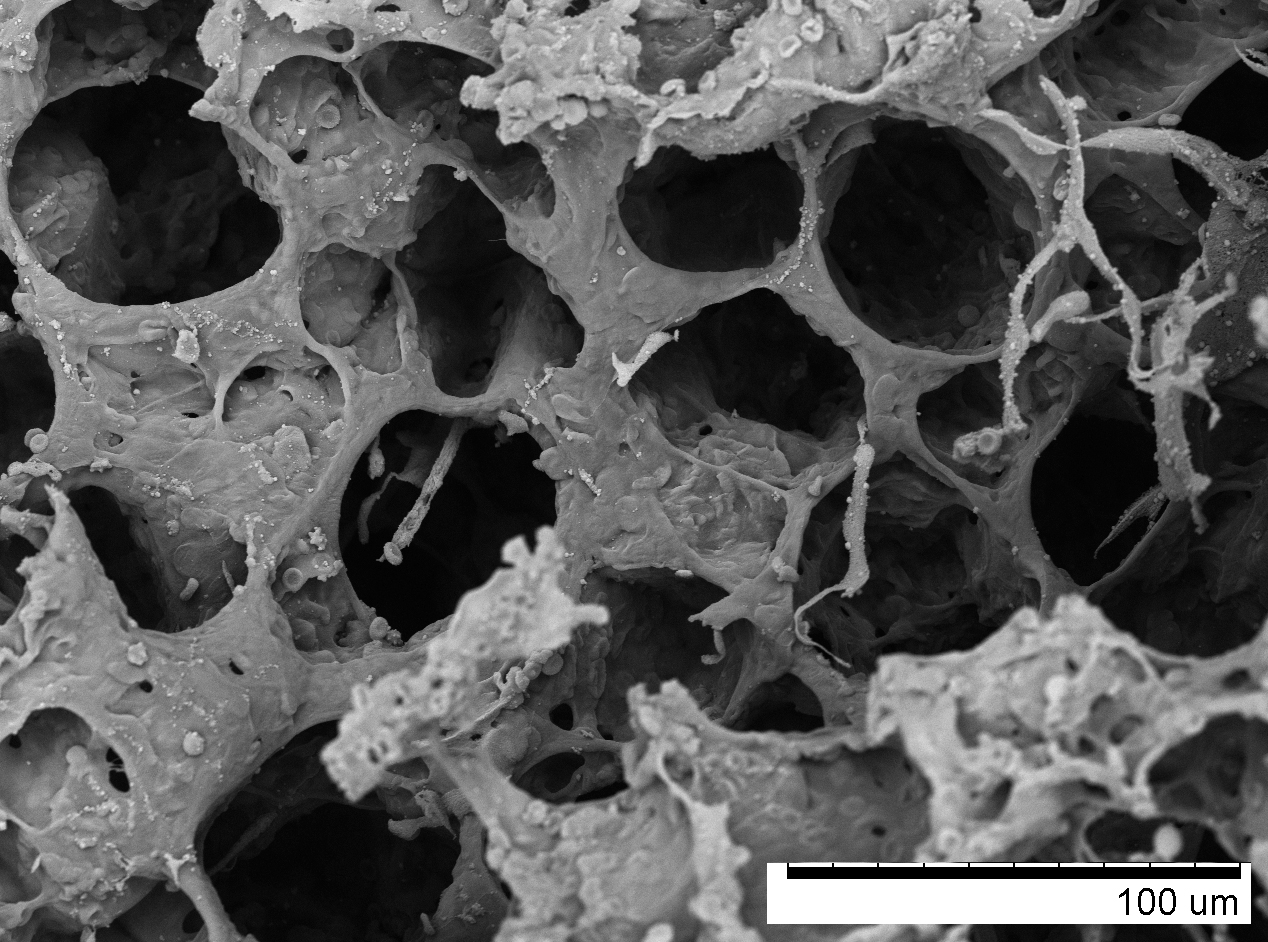

Continuum mechanics provides a convenient approach to the study of living systems with high spatial fidelity, but lung tissue poses unique challenges because intertwined alveoli and smaller airways constitute a highly porous, soft material that undergoes considerable deformations (see Figure 1). This type of tissue microstructure has motivated the development of poromechanical continuum formulations to model the gas-tissue interaction that occurs in the lungs during respiration. Some of the first attempts to model lung tissue through poromechanical lenses date back to the work of Piotr Kowalczyk in the early 1990s [11], which might represent the first effort to model lung tissue as a two-phase solid. Since then, researchers have used poromechanics to simulate the interaction between lung tissue deformation and gas flow on anatomical domains [4, 13]. However, the clinical applications of poromechanical lung models to predict pulmonary response to mechanical ventilation have only recently emerged [2]. These newer studies demonstrate that we can predict clinically relevant parameters—such as respiratory compliance and airway resistance—based on numerical simulations that are informed by a patient’s medical images.

Although these and other recent pulmonary modeling developments strongly support the theory that digital twins can transform respiratory medicine, lung models have not yet reached the necessary technological maturity to translate into bedside applications. Among other factors, predictiveness—the ability to deliver results that closely resemble patient response with minimal input data and before an intervention occurs—remains a grand challenge in the construction of digital twins in medicine.

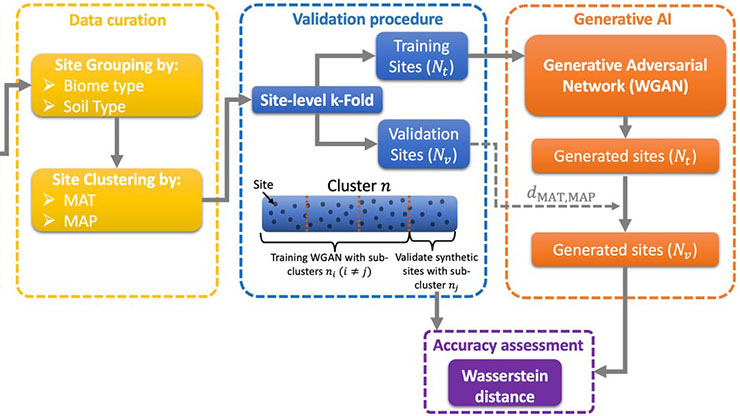

For many years, biological discovery has been driven by the structure-function paradigm, where structural features at the molecular and tissue scales explain the functions of organs and living systems. This area of study presents a unique opportunity for biomechanics and applied mathematics. Multiscale modeling theory enables the formulation of governing equations in living systems that incorporate microstructural information, which ultimately drives physiological function [6]. Assuming a periodic representation for alveolar tissue (see Figure 2), we can use two-scale asymptotic expansions on the fields of interest to analyze the poromechanical gas-structure interaction problem that governs alveolar mechanics [10]. This approach naturally yields governing equations for both the fine scale (alveolar structure) and coarse scale (lung tissue). These scales are connected by upscaling relationships that define the stress and permeability tensors at the coarse scale, which depend on the fine-scale properties and balance equations.

![<strong>Figure 2.</strong> Multiscale model of lung poromechanics. The fine scale considers the alveolar microstructure, which is governed by balance laws and gas-tissue interaction. Figure adapted from [2].](/media/pheb1zck/figure2.jpg)

The fine-scale problem requires the definition of a periodic unit cell. Based on histological observations, we can assume that the unit cell follows a tetrakaidekahedral platonic structure, which is periodic [9]. Such an idealized structure relies on parameters that summarize the alveolar architecture, including alveolar porosity, alveolar wall elasticity, and two other geometric parameters [7]. If we assume that the alveolar walls have a predominantly axial stress state, we can then solve the fine-scale problem as a nonlinear structural problem with a few degrees of freedom [8]. Comparisons of the effective behavior against direct numerical simulations of representative volume elements affirm that the upscaled micromechanical model accurately and efficiently predicts several loading states, thus confirming its predictive capabilities.

How do these multiscale models perform during the simulation of a lung that is connected to a mechanical ventilator? A sensitivity analysis of the alveolar porosity and alveolar wall elasticity parameters reveals that whole-lung simulations based on this multiscale approach yield a mechanical response that is strongly dependent on these two parameters. Increasing the alveolar porosity produces a softer, more compliant lung response to mechanical ventilation. In contrast, an increase in alveolar wall elasticity causes stiffer, less compliant mechanical behavior.

Interestingly, these results align well with routine observations in clinical practice. For example, lungs with pulmonary emphysema have larger alveoli due to breakdown of the alveolar walls, which leads to larger airspaces. As predicted by multiscale simulations, the mechanical response of emphysematous lungs is significantly more compliant than normal lungs [12]. In the case of fibrotic lungs, where alveolar tissue presents a higher-than-normal density of collagen fibers, the mechanical response is less compliant than in normal lungs — a phenomenon that is attributed to the stiffening effect that a higher density of collagen fibers confers to alveolar walls.

A multiscale lung model that seamlessly captures the impact of microstructural features on organ response is only the first step in the long road to the clinical translation of pulmonary digital twins. What is missing? First, computational lung models necessitate robust methods for personalization. Representation of the patient-specific lung anatomy is not enough, as material parameters that characterize the mechanical response of the lung tissue, airways, and surrounding structures are key to accurate predictions. To ensure patient safety, we need to infer these parameters from current clinical monitors and imaging technologies. Second, computational predictions of clinically relevant pulmonary parameters require broad clinical validation. Digital twins must be able to demonstrate accuracy when forecasting the reaction of ARDS lungs that respond differently depending on their pathology phenotype.

Ultimately, sound clinical evidence that pulmonary digital twins significantly improve clinical outcomes is a prerequisite for clinical adoption. As such, clinical trials that employ pulmonary digital twins must demonstrate a significant decrease in mortality across a wide population of patients.

These steps towards making digital twins a bedside technology are undoubtedly challenging, but it is more challenging to lose a loved one to ARDS while they are connected to mechanical ventilation.

Daniel Hurtado delivered an invited presentation on this topic at the 2025 SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, which took place last year in Fort Worth, Texas.

References

[1] Auld, S.C., Caridi-Scheible, M., Blum, J.M., Robichaux, C., Kraft, C., Jacob, J.T., … Murphy, D.J. (2020). ICU and ventilator mortality among critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit. Care Med., 48(9), e799-e804.

[2] Avilés-Rojas, A., & Hurtado, D.E. (2022). Whole-lung finite-element models for mechanical ventilation and respiratory research applications. Front. Physiol., 13, 984286.

[3] Bates, J.H.T. (2009). Lung mechanics. An inverse modeling approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Berger, L., Bordas, R., Burrowes, K., Grau, V., Tavener, S., & Kay, D. (2016). A poroelastic model coupled to a fluid network with applications in lung modelling. Int. J. Numer. Method Biomed. Eng., 32(1), e02731.

[5] Brower, R.G., Matthay, M.A., Morris, A., Schoenfeld, D., Thompson, B.T., & Wheeler, A. (2000). Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med., 342(18), 1301-1308.

[6] Collis, J., Brown, D.L., Hubbard, M.E., & O’Dea, R.D. (2017). Effective equations governing an active poroelastic medium. Proc. Math. Phy. Eng. Sci., 473(2198), 20160755.

[7] Concha, F, & Hurtado, D.E. (2020). Upscaling the poroelastic behavior of the lung parenchyma: A finite-deformation micromechanical model. J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 145(15), 104147.

[8] Concha, F., Sarabia-Vallejos, M., & Hurtado, D.E. (2018). Micromechanical model of lung parenchyma hyperelasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 112(10), 126-144.

[9] Fung, Y.C. (1988). A model of the lung structure and its validation. J. Appl. Physiol., 64(5), 2132-2141.

[10] Hurtado, D.E., Avilés-Rojas, N., & Concha, N. (2023). Multiscale modeling of lung mechanics: From alveolar microstructure to pulmonary function. J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 179, 105364.

[11] Kowalczyk, P. (1993). Mechanical model of lung parenchyma as a two-phase porous medium. Transp. Porous Med., 11(3), 281-295.

[12] Papandrinopoulou, D., Tzouda, V., & Tsoukalas, G. (2012). Lung compliance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm. Med., 2012, 542769.

[13] Patte, C., Genet, M., & Chapelle, D. (2022). A quasi-static poromechanical model of the lungs. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol., 21(2), 527-551.

[14] Villar, J., Blanco, J., Añón, J.M., Santos-Bouza, A., Blach, L., Ambrós, A., … Kacmarek, R.M. (2011). The ALIEN study: Incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med., 37(12), 1932-1941.

About the Author

Daniel E. Hurtado

Professor, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Daniel E. Hurtado is a professor at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile and a research affiliate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He earned his Ph.D. at the California Institute of Technology as a Fulbright Fellow and is internationally recognized for his work on computational modeling of the respiratory system and healthcare innovation, having received honors from the World Economic Forum and the World Council of Biomechanics.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.