Small Choices, Big Costs: The Influence of Vaccine Hesitancy and Behavior-driven Modeling on Pandemic Outcomes and Economic Burden

- When the next pandemic hits, will our biggest threat be the virus or the choices that people make in response?

- What is the real societal cost of delaying or refusing vaccination during an outbreak?

- What are the risks of ignoring real-world data on fear, misinformation, and loss of public trust, only to face collapsing vaccine efforts and out-of-control outbreaks?

These types of questions highlight the direct connection between shifting human behaviors and pandemic outcomes. To investigate this challenging area of study, we developed and analyzed a novel epidemiological-behavioral model that captures the impact of behavioral responses driven by fear, misinformation, and lack of trust on long-term disease dynamics, public health policies, and public health outcomes.

Numerous historical events reveal how misinformation-driven changes in human behavior interact with disease transmission, shaping pandemic trajectories and producing substantial economic burdens. For example, in the early 2000s, measles was largely eliminated in high-income countries like the U.S. due to widespread uptake of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. However, a 1998 study led by Andrew Wakefield [7] falsely linked MMR to autism [2, 4]. Though it was later debunked and retracted, the publication sparked widespread fear and vaccination rates plummeted, creating a resurgence of measles outbreaks [9].

In India, the near eradication of polio in the early 2000s was also nearly undone by vaccine hesitancy [5]. Misinformation in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar falsely claimed that the oral polio vaccine caused sterility in Muslim children. As a result, healthcare workersfaced significant community resistance and immunization campaigns stalled. Only through years of persistent community engagement and culturally tailored communication was India eventually declared polio-free in 2014.

Similarly, the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, which was introduced in the mid-2000s to prevent cervical cancer and other cancers, faced significant backlash in Japan after media reports sensationalized unverified side effects [3]. Although these claims lacked scientific basis, they triggered public fear and caused vaccination rates to drop from more than 70 percent to less than one percent. It took nearly a decade, substantial policy, and strong communication efforts before proactive HPV vaccination promotion resumed in 2022.

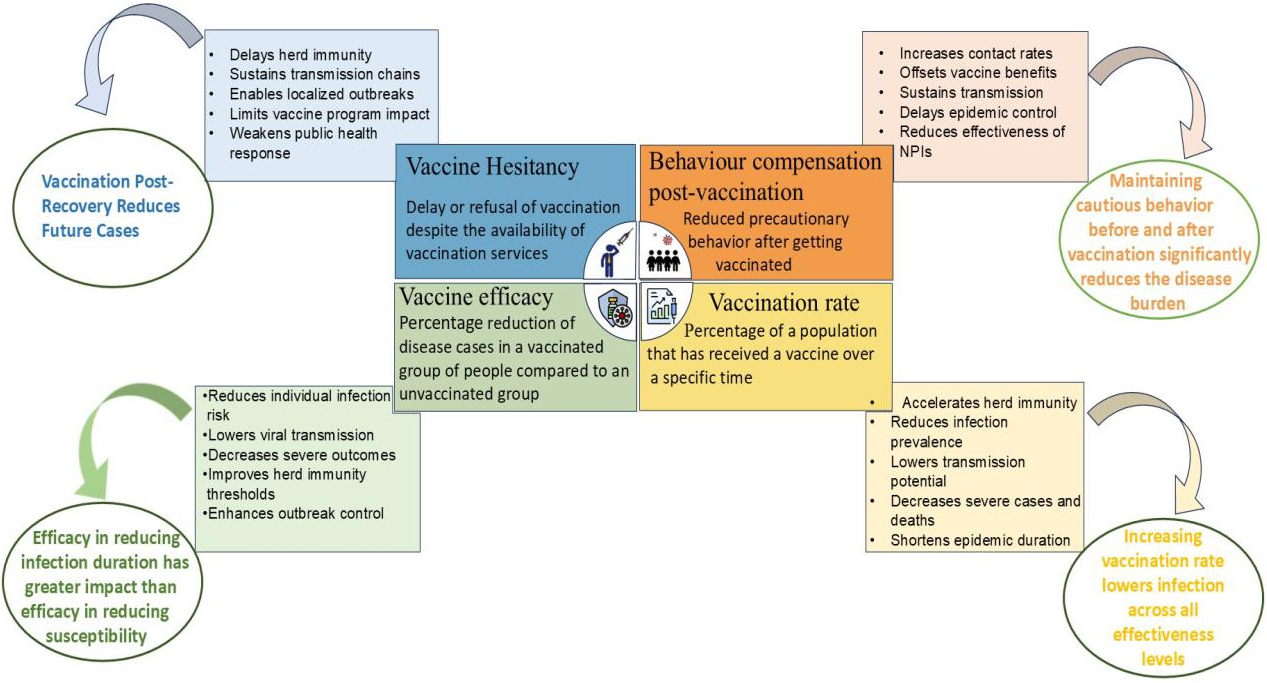

These examples affirm that vaccine success relies on both scientific efficacy and public behavior. As such, jointly modeling epidemiological and behavioral dynamics can help society better prepare for future pandemics. Protective behaviors such as masking and social distancing reduce disease transmission, while risky actions such as vaccine refusal increase it [1]. Vaccine hesitancy—often driven by misinformation, distrust, cultural beliefs, and fear of side effects—poses a major challenge to the control of infectious diseases. When individuals delay or refuse vaccination despite availability and expert recommendations, they undermine herd immunity, prolong virus circulation, and heighten the risk of outbreak [8]. Such conduct strains healthcare systems, disrupts immunization campaigns, and increases economic costs as evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic [6].

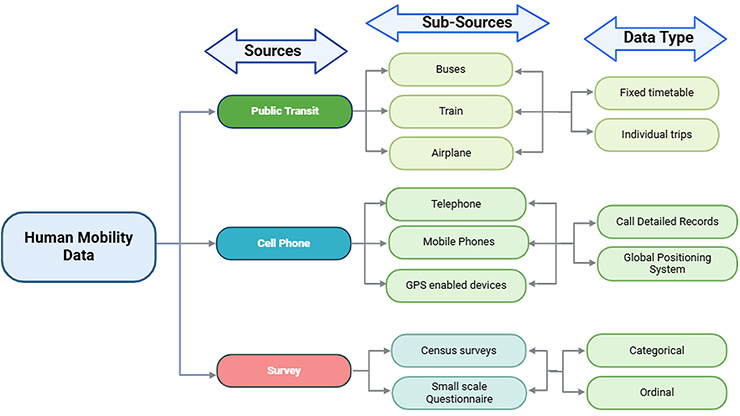

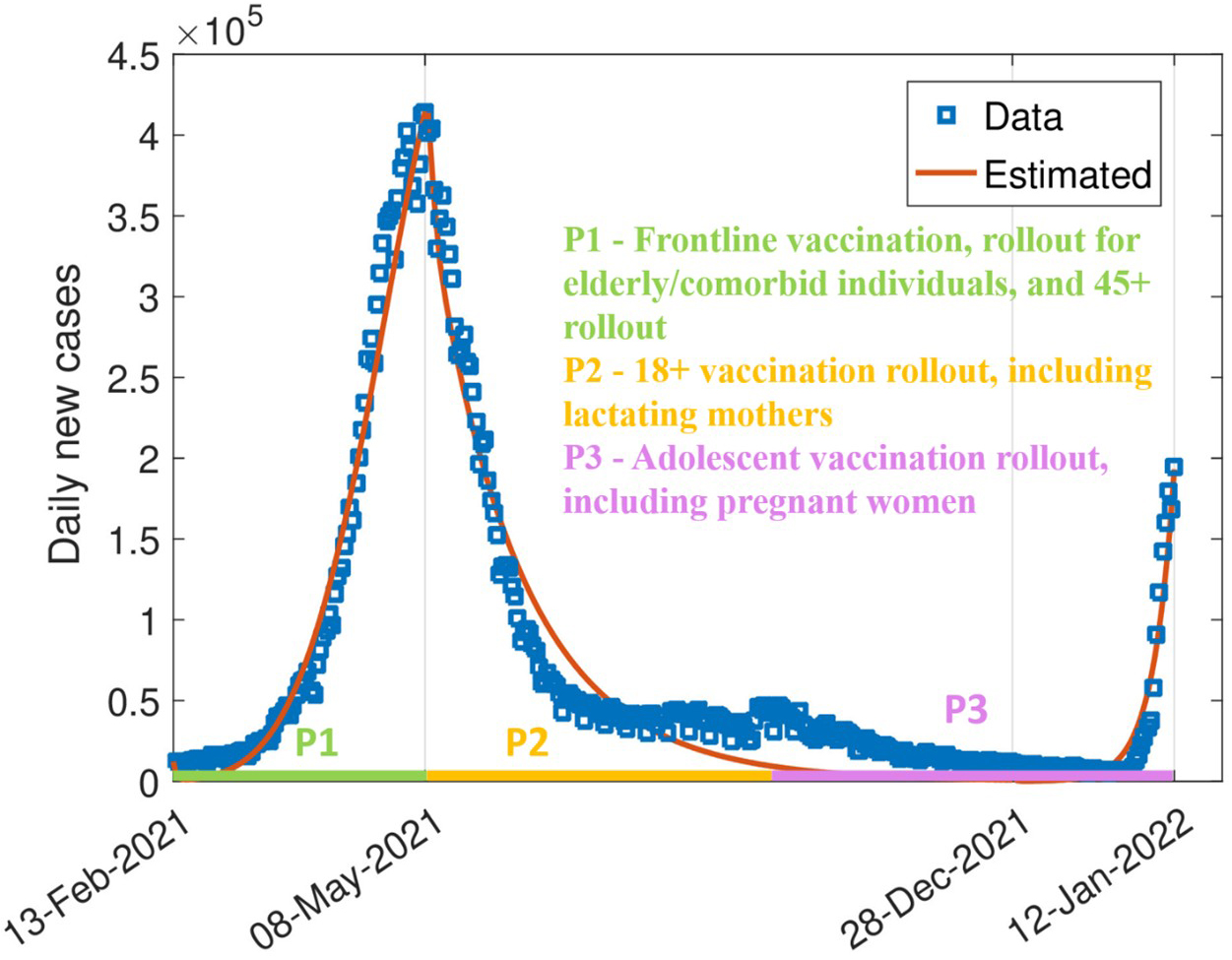

Most studies of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy rely on survey-based statistical or machine learning models, which fall short of capturing the dynamic interplay between behavior, misinformation, and disease spread. To address this gap, we created a comprehensive mathematical model that integrates vaccine hesitancy, post-vaccination behavioral change, and vaccine efficacy. Our model, which we calibrated with real-world COVID-19 data from India, captures feedback loops between individual behavior and epidemic progression, thus serving as a predictive tool for disease management (see Figure 1).

Modeling Framework

Our model divides the population into vaccine non-hesitant \((NH)\) and hesitant \((H)\) groups and uses a susceptible-infected-recovered framework with vaccination \((V)\) to describe disease dynamics. To quantify behavior-disease interactions, we define the following parameters:

- \(\gamma_1\): Shift from non-hesitant to hesitant susceptibles as risk perception declines

- \(\gamma_2\): Shift from hesitant to non-hesitant susceptibles as fear or awareness increases

- \(\gamma_3\): Infected individuals who become hesitant, preferring natural immunity over vaccination

- \(\gamma_4\): Similar behavioral shift among recovered individuals

- \(\theta_1\): Behavioral compensation after vaccination (e.g., increased contact).

The following system of differential equations captures the complete dynamics:

\[\begin{eqnarray} \frac{dS_H}{dt} &=& - \underbrace{{\lambda}{S_H}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Infection in hesitant} \end{array}} -\underbrace{{\gamma_2}{S_H}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Become non-hesitant} \\ \textrm{susceptibles due to fear} \\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\omega_1}{R_H}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning immunity in} \\ \textrm{hesitant recovered}\end{array}} + \underbrace{{\gamma_1}{S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{From non-hesitant} \\ \textrm{due to low spread} \\ \end{array}}\\ \frac{dS_{NH}}{dt} &=& - \underbrace{{\delta}{S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Vaccination} \\ \end{array}}-\underbrace{{\lambda(1-p)S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Infection} \\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{{\gamma_1}{S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{To hestitant due} \\ \textrm{to low spread}\end{array}} + \underbrace{{\gamma_2}{S_H}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{From hesitant} \\ \textrm{due to fear} \\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\sigma_3}{V_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning} \\ \textrm{immunity} \\ \textrm{in vaccinated}\\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\omega_2}{R_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning} \\ \textrm{immunity} \\ \textrm{in recovered}\\ \end{array}} \\ \frac{dI_H}{dt} &=& - \underbrace{{\lambda}{S_H}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Infection} \\ \textrm{in hesitant}\\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{{\sigma_1}{I_H}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Recovery} \\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{\mu_1I_H}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Disease-induced} \\ \textrm{death}\\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\gamma_3}{I_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Becoming hesitant} \\ \textrm{post infection} \\ \end{array}} \\ \frac{dI_{NH}}{dt} &=& \underbrace{{\lambda(1-p)S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Infection in} \\ \textrm{non-hesitant}\\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\lambda^V(1-p)V_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Infection in} \\ \textrm{vaccinated}\\ \end{array}} - \Bigg{(}\underbrace{\frac{\eta}{1-e_2}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Effective recovery}\\ \end{array}}+ \underbrace{\mu_2}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Disease-induced} \\ \textrm{death}\\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{\gamma_3}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Become} \\ \textrm{hesitant}\\ \end{array}}\Bigg{)}I_{NH} \\ \frac{dV_{NH}}{dt} &=& \underbrace{{\lambda^V(1-p)V_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Infection in} \\ \textrm{vaccinated}\\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\delta}{S_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Vaccination} \\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{{\sigma_3}{V_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning immunity} \\ \end{array}} \\ \frac{dR_H}{dt} &=& \underbrace{{\sigma_1}{I_H}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Recovery} \\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{{\omega_1}{R_H}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning immunity} \\ \end{array}} + \underbrace{{\gamma_4}{R_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Become hesitant} \\ \textrm{post-recovery}\\ \end{array}} \\ \frac{dR_{NH}}{dt} &=& \underbrace{\frac{\eta}{1-e_2}I_{NH}}_{\begin{array}{c} \textrm{Recovery}\\ \end{array}} - \underbrace{{({\omega_2}+{\gamma_4})R_{NH}}}_{\begin{array}{c}\textrm{Waning immunity} \\ \textrm{or become hesitant}\end{array}} \\ \end{eqnarray}\]

The model’s core lies in the force of infection \((\lambda)\): the rate at which susceptible individuals become infected. This rate is dependent on contact with both hesitant \(I_H\) and non-hesitant \(I_{NH}\) individuals and weighted by their behavior (e.g., mask use). For vaccinated individuals, we adjust it further \(({\lambda}^V)\) based on vaccine efficacy \((e_1)\) and behavioral compensation \(({\theta}_1).\)

Data Sources and Parameter Estimation

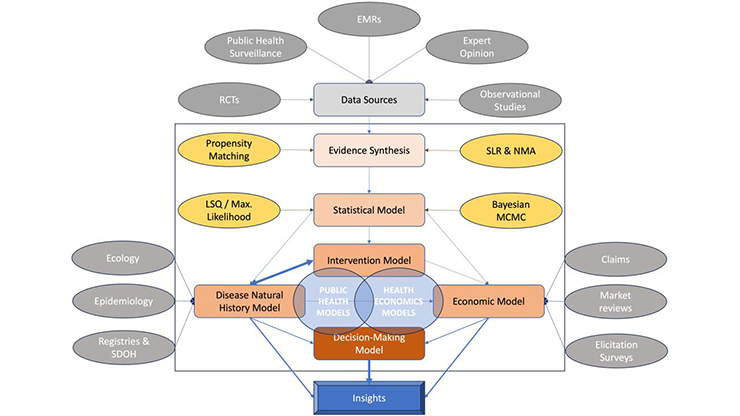

When a pandemic unfolds, the virus itself is only part of the story. Every infection curve reflects latent layers of human behavior that are driven by emotion, information, and trust. We used daily COVID-19 incidence data from the World Health Organization for India from February 2021 to January 2022 to calibrate behavioral shifts during phased vaccine rollouts. Because direct, real-time measures of vaccine hesitancy were unavailable, we employed Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which are well suited to estimate unobserved (latent) behavioral processes in complex, nonlinear models.

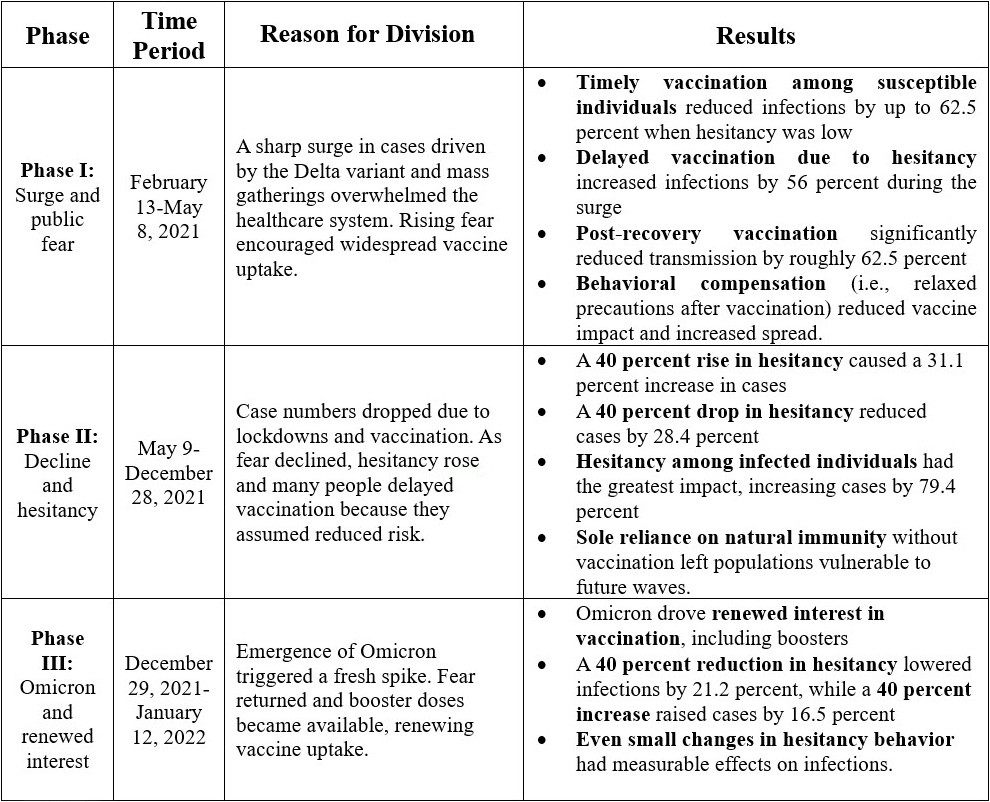

By analyzing hidden structures in daily case trajectories, we indirectly inferred vaccine hesitancy and post-vaccination risk compensation, thus providing a reliable representation of national-level epidemic trends. We also explicitly incorporated key milestones in India's phased vaccination campaign, including rollout in February 2021 for healthcare workers, elderly populations, and adults over 45 years of age, followed by universal adult eligibility in May 2021 and subsequent access for lactating mothers, pregnant women, and adolescents (see Figure 2). These stages shaped both vaccine access and population behavioral response.

Although MCMC is ideal for calibrating complex models, it demands careful validation. As such, we used adaptive Metropolis-Hastings algorithms and applied standard convergence diagnostics to ensure robust parameter estimation and simulate both the actual epidemic trajectory and counterfactual scenarios (i.e., what could have happened under different policies or behavioral shifts).

Key Findings

India’s experience with COVID-19 shows that while vaccination is a powerful tool, it is also a fragile shield. Our model reveals that unchecked hesitancy can trigger large surges of infection, even among previously infected individuals. As hesitancy declines and vaccination uptake increases, infection rates drop significantly, especially when combined with sustained protective behaviors like masking or social distancing. Improved vaccine effectiveness—such as shorter duration of illness—further reduces transmission, but misinformation or behavioral complacency—such as skipped doses—can quickly erode any vaccine gains. As such, vaccination campaigns require clear communication and behavioral nudges to sustain momentum. History clearly demonstrates that vaccine hesitancy has repeatedly stalled the eradication of diseases like smallpox, polio, and measles, and that same risk persists today.

Models like ours do more than predict trends; they can equip policymakers with actionable tools to expand coverage of vaccination services, curb outbreaks, and prepare for future pandemic waves. Ultimate success depends not only on medical innovation, but on people’s behavior after vaccination (see Figure 3).

Future Directions

Beyond COVID-19, this study highlights the urgent need for proactive and adaptable public health policies that address vaccine hesitancy, which is often driven by misinformation, cultural barriers, and limited awareness. Potential strategies include the following:

- Targeted public awareness campaigns to counter misinformation

- Mandatory vaccination in high-risk groups (e.g., healthcare workers)

- Incentive-based programs to encourage uptake among hesitant individuals

- Integration of mechanistic mathematical models and digital twin frameworks into real-time decision-making.

This framework is applicable to future pandemics and vaccine-preventable diseases like influenza, HPV, and polio. By explicitly modeling human behavior, policymakers can better anticipate challenges and design targeted, data-driven interventions. Digital twins—virtual representations of population-level disease and behavior dynamics—can further support scenario testing, policy optimization, and adaptive response planning. As vaccine hesitancy persists, such models will be essential for disease forecasting, mitigation, and prevention.

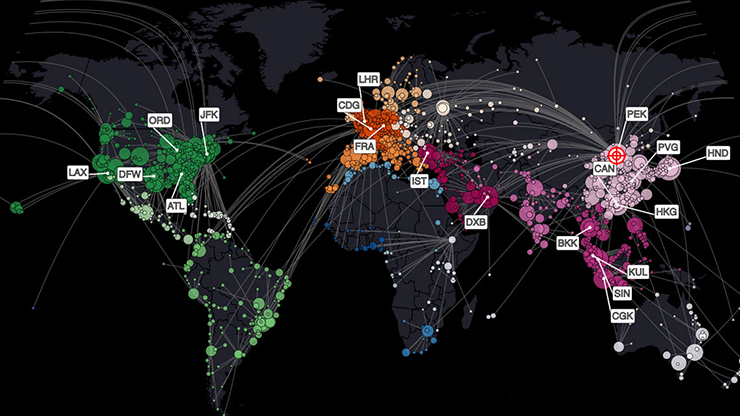

Artificial intelligence (AI) is also an emerging powerful tool that captures real-time behavioral dynamics that shape epidemic outcomes. While our study highlights the health and economic consequences and mechanisms of vaccine hesitancy, traditional surveillance systems often fail to detect and track rapid behavioral change. AI can help bridge this gap by analyzing social media, search trends, and mobility patterns to generate timely signals of behavior and attitude shifts. When combined with digital twin models, these AI-driven insights into epidemiological models enhances both predictive accuracy and response speed, allowing healthcare systems to anticipate, simulate, and respond before new waves materialize. The fusion of AI, digital twins, behavioral science, and infectious disease modeling has the potential to transform public health strategy and pandemic preparedness.

References

[1] Dubé, E., Vivion, M., & MacDonald, N.E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: Influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev. Vaccines, 14(1), 99-117.

[2] Funk, S., Salathé, M., & Jansen, V.A.A. (2010). Modelling the influence of human behaviour on the spread of infectious diseases: A review. J. R. Soc. Interface, 7(50),1247-1256.

[3] Normile, D. (2022, March 29). Japan reboots HPV vaccination drive after 9-year gap. Science, 376(6588), p. 14.

[4] Rao, T.S.S., & Andrade, C. (2011). The MMR vaccine and autism: Sensation, refutation, retraction, and fraud. Indian J. Psychiatry, 53(2), 95-96.

[5] Solomon, R. (2019). Involvement of civil society in India’s polio eradication program: Lessons learned. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 101(4 Suppl.), 15-20.

[6] Tanwar, K., Kumawat, N., Tripathi, J.P., Chauhan, S., & Mubayi, A. (2024). Evaluating vaccination timing, hesitancy and effectiveness to prevent future outbreaks: Insights from COVID-19 modelling and transmission dynamics. R. Soc. Open Sci.,11(11), 240833.

[7] Wakefield, A.J., Murch, S.H., Anthony, A., Linnell J., Casson, D.M., Malik, M., … Walker-Smith, J.A. (1998). Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children (RETRACTED). Lancet, 351(9103), 637-641.

[8] Wiyeh, A.B., Cooper, S., Nnaji, C.A., & Wiysonge, C.S. (2018). Vaccine hesitancy ‘outbreaks’: Using epidemiological modeling of the spread of ideas to understand the effects of vaccine related events on vaccine hesitancy. Expert Rev. Vaccines, 17(12), 1063-1070.

[9] Zucker, J. R., Rosen, J. B., Iwamoto, M., Arciuolo, R. J., Langdon-Embry, M., Vora, N. M., ... Barbot, O. (2020). Consequences of undervaccination — measles outbreak, New York City, 2018-2019. N. Engl. J. Med., 382(11), 1009-1017.

About the Authors

Komal Tanwar

Research scholar, Central University of Rajasthan

Komal Tanwar is a research scholar in the Department of Mathematics at the Central University of Rajasthan in India. Her research integrates mathematics, data-driven approaches, epidemiology, and human behavior to analyze infectious disease dynamics, evaluate vaccination strategies, and inform effective health policy.

Jai Prakash Tripathi

Professor, Central University of Rajasthan

Jai Prakash Tripathi is a professor of mathematics at Central University of Rajasthan in India. His research interests include mathematical biology and nonlinear dynamics in the context of ecological modeling and mathematical epidemiology. Tripathi uses a variety of mathematical techniques to study the nonlinear features of ecosystems and disease models, including stability, resilience, robustness, transient dynamics, bifurcations, periodicity, and oscillations.

Anuj Mubayi

Principal, NumericaIQ

Anuj Mubayi is a principal at NumericaIQ, a Fellow in Residence at the Intercollegiate Biomathematics Alliance, an honorary fellow at the Kalam Institute of Health Technology in India, and a scientific advisor to Kalam Experts. He previously served as director of the Mathematical and Theoretical Biology Institute and held faculty appointments at Arizona State University. A health decision analyst and mathematical modeler, Mubayi’s work integrates health economics, disease dynamics modeling, and real-world evidence to inform policy and healthcare strategy. He has held senior leadership roles in healthcare consulting within health economics and outcomes research teams and serves on the editorial boards of several international journals, including Letters in Biomathematics, Dynamical Systems, and the International Journal of Health Technology and Innovation.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.