Using Surrogate Models to Boost Ice Sheet Simulations Under Uncertainty

Ice sheet simulations face vast parametric uncertainties that propagate into sea level rise projections, which then influence policy decisions. Classic uncertainty quantification (UQ) methods are prohibitively expensive due to the accumulating computational cost of many high-fidelity samples. As an alternative, multifidelity UQ (MFUQ) methods shift the computational load onto fast, low-fidelity surrogate models while guaranteeing statistically unbiased estimates of the high-fidelity expectation. For example, when approximating Greenland’s expected contribution to sea level rise at \(\pm\)1 millimeter of accuracy, we found that multifidelity methods can decrease the computational cost by almost two orders of magnitude with readily available surrogates, such as physical approximations and coarser grids [1]. Additionally, we can further increase MFUQ’s performance by expanding the variety and quality of the employed surrogates.

To this end, we introduce a data-driven, physics-informed approach that pairs the speedup of reduced-order models (ROMs) with local, full-order adjustments for accuracy [3]. When we applied our approach to a model of Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier with varying melting parameters at the ice-ocean interface, it accurately predicted the grounding line’s retreat with an 8\(\times\) computational speed-up (see Figure 1). Overall, our results demonstrate surrogate modeling’s ability to enable UQ at scale in computational glaciology.

Multifidelity Uncertainty Quantification

Surrogate models are pervasive in glaciology literature. The earliest surrogate models simplified physical descriptions of ice dynamics; researchers have since analyzed their accuracy to thoroughly understand model limitations. In recent years, machine learning models and other emulators have further reduced computational expenses — albeit at the cost of additional approximation error, training time, and the occasional loss of physical interpretability. While surrogate models can approximate statistics of high-fidelity outputs that are prohibitively expensive, replacing a high-fidelity model with a surrogate introduces statistical bias.

We explore the issue of statistical bias for large-scale ice sheet simulations in our recent work [1]. Using an open-source glaciology community code called the Ice-sheet and Sea-level System Model (ISSM) [6], we simulate the ice mass loss and associated sea level rise of the Greenland ice sheet. We assume a moderate climate scenario (SSP1-2.6), as specified in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report [7]. We specifically consider two sources of uncertainty—geothermal heat flux and the basal friction field—and tailor their probability distributions to the variations in different data sets. Both fields are only indirectly observable via ice core measurements and ice surface velocity; as such, their associated uncertainty is large, which is reflected in the simulation’s large variance (see Figure 2).

![<strong>Figure 2.</strong> Multifidelity uncertainty quantification (MFUQ) methods leverage the computational speedup of surrogate models to compute unbiased estimates of the high-fidelity mean with improved accuracy. Figure adapted from [1].](/media/mydjzzq4/figure2.jpg)

For a computational budget of five solves, a Monte Carlo (MC) simulation is only accurate up to \(\pm\)5.3 millimeters of sea level rise at 95 percent confidence. Replacing the expensive three-dimensional velocity solver with a two-dimensional surrogate—a common physical approximation in computational glaciology—can drastically reduce simulation costs of the model, but the introduced bias is nonnegligible (see Figure 2).

MFUQ utilizes the statistical correlation between models to leverage the computational benefits of surrogates while guaranteeing an unbiased estimate of the high-fidelity quantity of interest. For example, the multifidelity MC (MFMC) method uses a single surrogate output \(\tilde{s}\) of the high-fidelity output \(s\) to approximate

\[\mathbb{E}[s] = \mathbb{E}[s] + \alpha \mathbb{E}[\tilde{s}] - \alpha \mathbb{E}[\tilde{s}] \approx \hat{s}_{\rm{MFMC}} := \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m s(\theta_i) + \frac{\alpha}{\tilde{m}} \sum_{i=1}^{\tilde{m}} \tilde{s}(\theta_i) - \frac{\alpha}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \tilde{s}(\theta_i).\]

Here, \(\tilde{m} > m \ge 1\) samples \(\theta_1, \dots, \theta_{\tilde{m}}\), which is shared between the models [8]. Under mild assumptions on the model correlation and with optimized weights \(\alpha\) and sample sizes \(m, \tilde{m}\) [10], the MFMC estimator \(\hat{s}_{\rm{MFMC}}\) achieves a finer accuracy than MC sampling for the same computational budget. Other MFUQ approaches include multilevel MC (MLMC) [2] and the multilevel best linear unbiased estimator (MLBLUE) [11].

For our MFUQ study, we set up 12 surrogates through mesh coarsening, physical approximations, and different training procedures [1]. The MFMC and MLMC estimators select from these models and reduce the width of the 95 percent confidence interval from \(\pm\)5.3 millimeters with MC sampling to \(\pm\)1.7 millimeters for the same computational budget of five high-fidelity model solves. MLBLUE achieves an even larger but less stable reduction in uncertainty at \(\pm\)0.5 millimeters (see Figure 2).

This experimentation demonstrates the current capabilities of MFUQ with readily available surrogates. The construction of MFUQ estimators will further increase this power as more surrogates become available. However, it is important to remember that a quality surrogate strikes a balance between computational speedup and statistical correlation to the high-fidelity model.

Physics-informed ROMs for Fast, Accurate Parametric Predictions

Model order reduction aims to reduce the computational complexity of mathematical models in numerical simulations. The construction of ROMs is especially beneficial for systems whose dynamics evolve in a low-dimensional space. In many such cases, we can feasibly solve a compressed version of the original, high-dimensional system of state dimension \(n\). This ROM has \(r \ll n\) degrees of freedom \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}^r\), which we derive from a projection of the original state vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\). Using a linear projection basis \(\mathbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times r}\), we are able to derive a low-dimensional approximation of the state \(\hat{x}\) as \(x \approx \mathbf{V} \hat{x}\). We can then directly encode this process into the discretized, full-order model that governs the dynamics of \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\) when it is explicitly available. Such methodologies are deemed intrusive; in contrast, non-intrusive model reduction directly infers a ROM that governs the dynamics of \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}^r\) from numerical data.

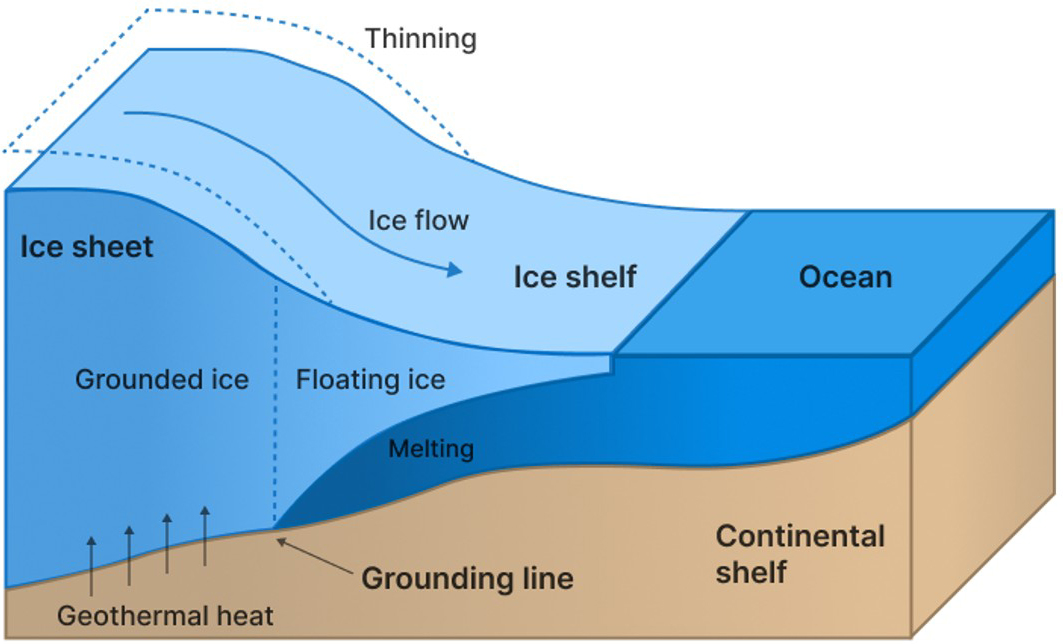

Researchers typically use legacy code to numerically simulate the nonlinear dynamical systems that arise in computational glaciology. But since the operators are not explicitly accessible to the end user, doing so hinders the application of intrusive ROMs. Physics-informed, data-driven modeling bridges this gap by leveraging simulation data and physical knowledge to enable the inference via ROM. Moreover, spatially localized system nonlinearities and transport-dominated phenomena are present in ice glacier dynamics, where ice flows towards the ocean; these features can impact the singular value decay of the training data matrix and yield a prohibitively high ROM dimension \(r.\)

![<strong>Figure 3.</strong> Nonintrusive modeling for dynamical systems with localized features Application of the inferred coupled operator inference and sparse full-order model (OpInf-sFOM) to parametric ice thickness dynamics of the Pine Island Glacier in Antarctica. <strong>3a.</strong> Data snapshots collections. <strong>3b.</strong> Coupled operator inference and sparse, full-order model (OpInf-sFOM) formulation. <strong>3c.</strong> Parametric ice thickness predictions. Figure courtesy of [3].](/media/wtdg4p4i/figure3.jpg)

We present a methodology for nonintrusive model reduction of systems with spatially localized dynamics and apply it to ice thickness dynamics of Antarctica’s Pine Island Glacier [3]. The main idea is to isolate regions that are dominated by transport phenomena or localized nonlinearities. In such regions, we employ an adjacency-based, sparse, full-order model (sFOM) to infer system dynamics at the full-order level [4]. For the complementary subdomain where the singular value decay is fast, we use operator inference (OpInf) [5, 9] to learn a non-intrusive ROM (see Figure 3). To promote stability of both inferred models, we introduce a regularization strategy that is based on the Gershgorin circle theorem.

Using the ISSM, we obtain simulation data for the ice thickness equation under varying melt parameters at the ice-ocean interface of the Pine Island Glacier. By segregating the glacier domain into regions of (i) fast ice melt and transport and (ii) grounded ice with slower dynamics, we infer a coupled OpInf-sFOM model with 37 percent of the original ISSM model’s degrees of freedom from two simulations for extreme ice melt rates (see Figure 3). Our parametric OpInf-sFOM predictions of ice thickness dynamics match numerical simulation results with an accuracy of more than 95 percent for unseen ice melt rate values. They correctly capture the main features of ice motion and melt over time while achieving approximately an 8\(\times\) online speedup when compared to the ISSM code.

Outlook

Our works achieve fast and accurate predictions of ice dynamics by leveraging MFUQ and a non-intrusive ROM. The results showcase the potential use of new applied mathematics and computational engineering approaches in large-scale numerical simulations. Synergy between experts in applied mathematics, computer science, physics, and engineering is therefore essential to efficiently tackle contemporary, challenging computational glaciology problems.

References

[1] Aretz, N., Gunzburger, M., Morlighem, M., & Willcox, K. (2025). Multifidelity uncertainty quantification for ice sheet simulations. Comput. Geosci, 29, 5.

[2] Giles, M.B. (2015). Multilevel Monte Carlo methods. Acta Numer., 24, 259-328.

[3] Gkimisis, L., Aretz, N., Tezzele, M., Richter, T., Benner, P., & Willcox, K.E. (2025). Non-intrusive reduced-order modeling for dynamical systems with spatially localized features. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng., 444, 118115.

[4] Gkimisis, L., Richter, T., & Benner, P. (2024). Adjacency-based, non-intrusive model reduction for vortex-induced vibrations. Comput. Fluids, 275, 106248.

[5] Kramer, B., Peherstorfer, B., & Willcox, K.E. (2024). Learning nonlinear reduced models from data with operator inference. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech., 56, 521-548.

[6] Larour, E., Seroussi, H., Morlighem, M., & Rignot, E. (2012). Continental scale, high order, high spatial resolution, ice sheet modeling using the Ice Sheet System Model (ISSM). J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf, 117(F1).

[7] Lee, H., Calvin, K., Dasgupta, D., Krinner, G., Mukherji, A., Thorne, P., … Zommers, Z. (2023). Climate change 2023 synthesis report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf.

[8] Ng, L.W.T., & Willcox, K.E. (2014). Multifidelity approaches for optimization under uncertainty. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng., 100(10), 746-772.

[9] Peherstorfer, B., & Willcox, K. (2016). Data-driven operator inference for nonintrusive projection-based model reduction. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng., 306, 196-215.

[10] Peherstorfer, B., Willcox, K., & Gunzburger, M. (2016). Optimal model management for multifidelity Monte Carlo estimation. SIAM J. Sci. Comput., 38(5), A3163-A3194.

[11] Schaden, D., & Ullmann, E. (2020). On multilevel best linear unbiased estimators. SIAM/ASA J. Uncertainty Quantification, 8(2), 601-635.

About the Authors

Leonidas Gkimisis

Ph.D. student, Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems

Leonidas Gkimisis is a Ph.D. student in the Computational Methods in Systems and Control Theory group at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems in Germany. He holds an MSc in mechanical engineering from the National Technical University of Athens in Greece and an MRes in fluid dynamics from the Von Karman Institute for Fluid Dynamics in Belgium.

Nicole Aretz

Postdoctoral fellow, University of Texas at Austin

Nicole Aretz is a postdoctoral fellow at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests include physics-based reduced modeling, forward and inverse multifidelity uncertainty quantification, and optimal experimental design.

Marco Tezzele

Assistant professor, Emory University

Marco Tezzele is an assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics at Emory University and a member of Emory’s Scientific Computing Group. His research interests include digital twins, data-driven reduced order methods, parameter space reduction techniques, scientific machine learning, and structural optimization in naval engineering.

Thomas Richter

Full professor, Otto von Guericke University

Thomas Richter is a full professor at the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg in Germany, where he leads the Numerics in Applications research group in the Institute for Analysis and Numerics. His research focuses on numerical methods for partial differential equations, such as adaptive finite element methods and multiphysics applications.

Peter Benner

Director, Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems

Peter Benner is a director at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems, an honorary professor at the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg in Germany, and a SIAM Fellow. His research focuses on model order reduction, numerical linear algebra, and control theory for large-scale systems.

Karen E. Willcox

Director, Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences

Karen E. Willcox is director of the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences, Associate Vice President for Research, and a professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at the University of Texas at Austin. She is also an external professor at the Santa Fe Institute and a SIAM Fellow.

Related Reading

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.