Causal Effects of Media and Twitter Advocacy on Firearm Purchases

Firearm-related mortality is a leading cause of death in the U.S., surpassing fatalities from motor vehicle crashes [2]. Yet despite this significant public safety risk, Americans continue to purchase guns. In fact, the United States Firearms Commerce estimates that the national stock reached 393 million firearms in 2017 — more than the entire U.S. population [1]. American gun owners overwhelmingly acknowledge protection for themselves and their families as their primary reason for purchasing firearms [3], citing fear of violent crime and mass shootings. While advocacy groups on social media may capitalize on these fears to influence firearm acquisition, the simultaneous effects of these variables have not been explored in a causal framework.

![<strong>Figure 1.</strong> Daily time series of the variables in our study, with the application of a 30-day moving average filter for clarity. Vertical lines correspond to the following U.S.-based mass shootings (left to right): Sandy Hook Elementary School (12/14/2012 in Newtown, Conn.), Fort Hood (4/2/2014 near Killeen, Texas), Inland Regional Center (12/2/2015 in San Bernardino, Calif.), Pulse Nightclub (6/12/2016 in Orlando, Fla.), Route 91 Harvest Music Festival (10/1/2017 in Las Vegas, Nev.), Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (2/14/2018 in Parkland, Fla.), Borderline Bar and Grill (11/7/2018 in Thousand Oaks, Calif.), and Walmart (8/3/2019 in El Paso, Texas). <strong>1a.</strong> Media coverage of firearm laws and regulations, mass shootings, and violent crime. <strong>1b.</strong> Tweets by pro- and anti-regulation organizations. <strong>1c.</strong> Background checks for firearm purchases. Figure courtesy of [6].](/media/gxyh5jd0/figure1.jpg)

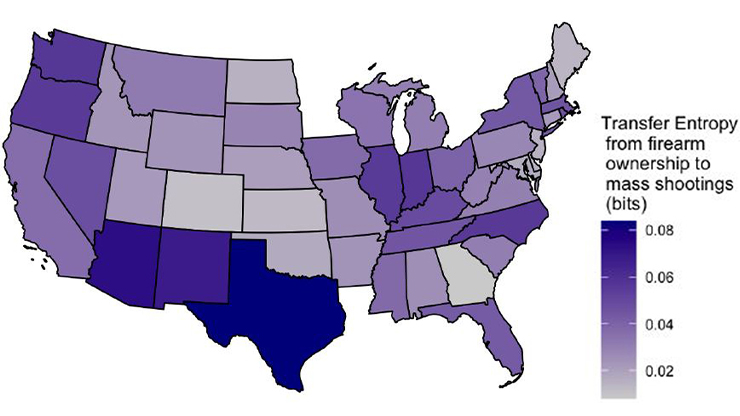

In a recent study [6], we investigated the effect of media coverage of firearm laws and regulations, mass shootings, and violent crimes as well as the Twitter (now X) activity of anti- and pro-regulation advocacy groups on short-term firearm acquisition in the U.S. We collected daily time series data for six key variables from 2012 to 2020, including media coverage of (i) firearm laws and regulations, (ii) mass shootings, and (iii) violent crimes; (iv) tweets by pro-regulation organizations and (v) tweets by anti-regulation organizations; and (vi) background checks as a proxy for firearm purchases. We then employed the PCMI+ framework to investigate their simultaneous casual relationships [5].

Because there is no national database of firearm ownership in the U.S., the true number of firearms must be inferred from survey data, manufacturing records, background checks, commercial records, and other data sources. Before purchasing a firearm, buyers must complete a background check form, the results of which are anonymized and released as publicly available data in the FBI's National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). Researchers can therefore use NICS data as an indirect measure for gun purchases.

We measured the three media-related variables (i-iii) by using the ProQuest search engine to count the number of relevant newspaper articles that published each day. To ensure ideological and geographic diversity, we selected 10 major newspapers across U.S. regions and political leanings. This approach ensured coverage of the entire continental U.S. while avoiding overrepresentation of any one region or perspective.

To quantify the online activity of advocacy groups, we turned to Twitter (now X), which acts as a “thermometer” of public discourse due to its real-time responsiveness to current events [8]. We utilized the “Social Bearing” research tool—which has since been discontinued—to identify the most-followed organizational accounts that advocate for or against firearm regulation based on keyword usage and follower counts. We included only institutional accounts with clear stances on gun policy and more than 5,000 followers; the final set comprised nine anti-regulation and 11 pro-regulation organizations. For groups like the National Rifle Association that operate multiple accounts, we selected the primary national account with the broadest reach. Using daily tweet counts, we generated time series of social media activity for each side (see Figure 1).

Next, we employed the PCMCI+ framework to perform causal analysis on the detrended and deseasonalized time series [5]. PCMCI+ begins with a complete graph \(G,\) where each node \(X_{t_n}\) represents the time series of a variable at a certain time delay. The subscript \(n\in(1,2,...,N)\) corresponds to a variable, and the superscript \(t\in(T,T-1,...,T-\tau)\) corresponds to a delay of the variable such that \(N\) is the total number of variables, \(T\) is the entire time series length, and \(\tau\geq 0\) is the maximum delay for which the algorithm tests. The algorithm considers the simultaneous application of all specified delays on all variables, thereby controlling for autocorrelations within each time series. It is based on the seminal Peter-Clark algorithm [7] and the concept of momentary conditional independence, which is inspired by the information-theoretic measure of momentary information transfer. We discover the algorithm’s “skeleton” by heuristically testing pairwise independence between variables — and later, independence between variables that are conditioned on a set of parents that are updated in each iteration of the algorithm.

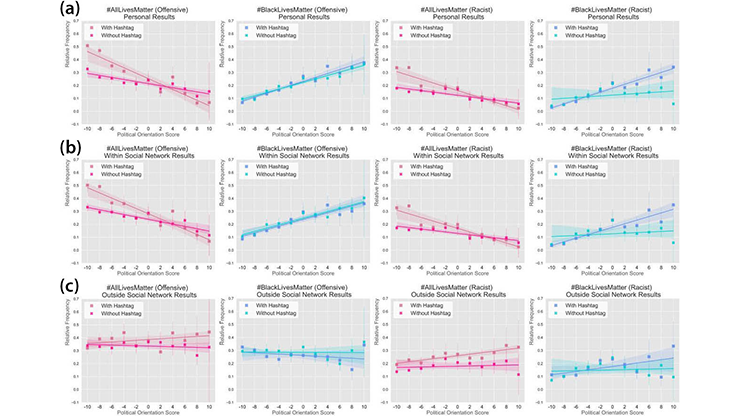

Our causal analysis revealed four significant links that involve the activity of advocacy groups on Twitter (see Figure 2). We found that media coverage of firearm laws and regulations preceded tweets by pro-regulation organizations by two days (link \(e\)). Interestingly, this effect was negative, thus suggesting that pro-regulation groups may attempt to raise awareness of legislative activity precisely when it is underreported in mainstream media. Consistent with this pattern, our results did not support the hypothesis that pro-regulation organizations capitalize on mass shootings or violent crimes to amplify their messaging.

![<strong>Figure 2.</strong>Causal diagram for the six variables under consideration, courtesy of PCMCI+. The link colors reflect the time delay between the two variables that they connect. Black links represent contemporaneous associations (zero-day delay), and square endings indicate that the link in question is non-orientable. Red, teal, blue, and orange arrows respectively reflect associations with one, two, six, and seven days; the analysis did not recover links for delays of three, four, and five days. Figure courtesy of [6].](/media/tj3l2lai/figure2.jpg)

In contrast, anti-regulation organizations displayed stronger and more direct effects. Their activity on Twitter was followed by increases in media coverage of violent crime with a two-day lag (link \(g\)). Although these groups tend to reduce posting after mass shootings or high-profile violent crimes, their sustained emphasis on legislative issues appears to influence the way in which violent crime stories are subsequently framed in the media. The activity of anti-regulation organizations was also bidirectionally associated with background checks (links \(j\) and \(k\)). The causal direction from tweets to background checks (link \(j\)) is particularly intuitive, as posts by anti-regulation groups likely resonate with followers who represent potential firearm buyers, thereby driving purchases. The reverse association (link \(k\)) suggests the presence of feedback from spikes in firearm acquisition in the social media activity of anti-regulation groups.

Overall, our causal diagram demonstrates that short-term firearm acquisition is most strongly influenced by the lobbying efforts of anti-regulation organizations on social media, along with media coverage of firearm laws and violent crime. In contrast, media coverage of mass shootings and the Twitter activity of pro-regulation organizations did not show direct short-term causal effects on background checks. These findings are consistent with earlier research that used monthly data to identify a causal link from media coverage of firearm control to background checks [4] — a result that our daily resolution analysis now confirms and extends.

Our study indicates that while media coverage of violent crimes and firearm regulations may influence citizens’ decisions to purchase a weapon, the social media activity of relevant interest groups has direct implications as well. Since potential firearm owners likely subscribe to anti-regulation channels, these organizations (not pro-regulation groups) directly influence firearm acquisition. With the understanding that media coverage of violent crime may drive both firearm acquisition and the activity of anti-regulation organizations, we encourage legislators and policymakers to target those aspects of the network in their messaging. For example, media literacy initiatives could help people engage with emotionally charged news about violent crime — possibly reducing impulsive, fear-driven firearm purchases. Additionally, social media platforms could implement transparency measures for political advocacy campaigns to ensure that advocacy group content that lacks sound scientific evidence is not disproportionately amplified through algorithmic bias. Finally, community-based violence prevention programs can provide alternative pathways to reduce gun-related crime. Collectively, these targeted interventions could address key drivers of firearm acquisition while maintaining a balanced approach that respects constitutional rights.

Kevin Slote delivered a poster presentation on this research at the 2025 SIAM Conference on Applications of Dynamical Systems, which took place in Denver, Colo., last May.

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under grant no. CMMI-2009329.

References

[1] Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (2018). Firearms commerce in the United States: Annual statistical update 2018. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.atf.gov/resourcecenter/docs/report/firearmscommercestatisticalupdate20185087-24-18pdf/download.

[2] Kochanek, K.D., Murphy, S.L., Xu, J., & Arias, E. (2019). Deaths: Final data for 2017. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 68(9), 1-77.

[3] PEW Research Center. (2023, August 16). For most U.S. gun owners, protection is the main reason they own a gun. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/08/16/for-most-u-s-gun-owners-protection-is-the-main-reason-they-own-a-gun.

[4] Porfiri, M., Sattanapalle, R.R., Nakayama, S., Macinko, J., & Sipahi, R. (2019). Media coverage and firearm acquisition in the aftermath of a mass shooting. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3(9), 913-921.

[5] Runge, J. (2020). Discovering contemporaneous and lagged causal relations in autocorrelated nonlinear time series datasets. In Proceedings of the 36th conference on uncertainty in artificial intelligence (pp. 1388-1397). Proceedings of Machine Learning Research.

[6] Slote, K., Daley, K., Succar, R., Barak Ventura, R., Porfiri, M., & Belykh, I. (2025). How advocacy groups on Twitter and media coverage can drive US firearm acquisition: A causal study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Nexus, 4(6), pgaf195.

[7] Spirtes, P., & Glymour, C. (1991). An algorithm for fast recovery of sparse causal graphs. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev., 9(1), 62-72.

[8] Succar, R., Ramallo, S., Das, R., Barak Ventura, R., & Porfiri, M. (2024). Understanding the role of media in the formation of public sentiment towards the police. Commun. Psychol., 2(1), 11.

About the Authors

Kevin Slote

Research professor, Clarkson University

Kevin Slote is a research professor in the Clarkson Center for Complex Systems Science at Clarkson University. He holds a Ph.D. in applied mathematics from Georgia State University.

Kevin Daley

Postdoctoral fellow, U.S. Naval Research Laboratory

Kevin Daley is a postdoctoral fellow at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

Rayan Succar

Ph.D. student, New York University

Rayan Succar is a Ph.D. student in the Center for Urban Science and Progress at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering.

Roni Barak Ventura

Assistant professor, New Jersey Institute of Technology

Roni Barak Ventura is an assistant professor in the School of Applied Engineering and Technology at the New Jersey Institute of Technology’s Newark College of Engineering.

Maurizio Porfiri

Institute Professor, New York University

Maurizio Porfiri is an Institute Professor in the Tandon School of Engineering at New York University (NYU) and director of NYU's Center for Urban Science and Progress.

Igor Belykh

Distinguished University Professor, Georgia State University

Igor Belykh is a Distinguished University Professor of Applied Mathematics in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at Georgia State University.

Stay Up-to-Date with Email Alerts

Sign up for our monthly newsletter and emails about other topics of your choosing.